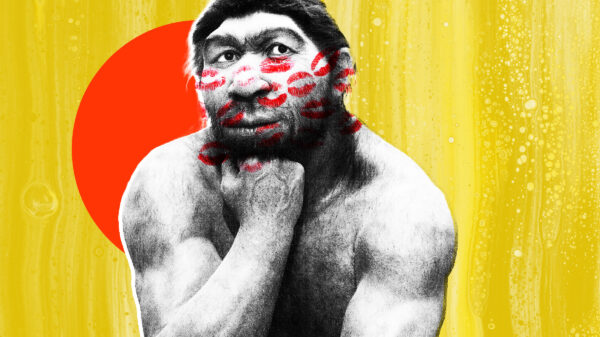

Researchers at the Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) have made a significant breakthrough by successfully using human skin cells to create fertilizable eggs. This innovative approach could potentially revolutionize fertility treatments. The findings, published on March 15, 2024, in the journal Nature Communications, detail how scientists took the nucleus from a skin cell and transplanted it into a donor egg that had been stripped of its own nucleus.

The research team produced a total of 82 functional human oocytes, which are immature egg cells. These eggs were then fertilized in a laboratory setting. The result is an egg that shares genetic material with the individual who provided the skin cell, capable of being fertilized with sperm from another person. According to Dr. Paula Amato, a co-author of the study and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at OHSU, this advancement could enable older women or those who have lost their eggs due to medical conditions, such as cancer treatment, to conceive genetically related children.

Dr. Amato stated, “This would allow older women, or women without eggs for any reason, to have a genetically related child. In addition, it would allow same-sex couples to have a child genetically related to both partners.”

Challenges and Future Research

Despite the promising nature of this research, there are considerable challenges that need to be addressed before clinical applications can be realized. The primary hurdle was ensuring that the reprogrammed egg had the correct number of chromosomes. In human reproduction, eggs and sperm each contain 23 chromosomes, half the total found in typical human cells. The research team developed a method they called “mitomeiosis” to eliminate the extra chromosomes, successfully leaving a functional egg cell.

However, fewer than 9% of the eggs created reached the blastocyst stage of embryo development, which typically occurs five to six days after fertilization. This is the stage when embryos are generally transferred to the uterus during in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment. All resulting embryos were found to be chromosomally abnormal, raising concerns about their viability for healthy pregnancies. Dr. Amato cautioned that these embryos would not be expected to develop into healthy babies and would likely stop progressing prematurely.

The study authors emphasized the need for extensive further research to ensure the safety and efficiency of this technique before it can be applied in clinical settings. Understanding how chromosomes pair and separate is crucial for creating eggs with the correct number of chromosomes.

Even in natural reproduction, only about a third of embryos develop to the blastocyst stage, noted Shoukhrat Mitalipov, director of the OHSU Center for Embryonic Cell and Gene Therapy. He stated, “At this stage, it remains just a proof of concept, and further research is required to ensure efficacy and safety before future clinical applications.”

Cautious Optimism from Experts

Other experts in the field, such as Amander Clark, a professor of molecular, cell, and developmental biology at the University of California, Los Angeles, shared a cautious optimism regarding the research. Although the study represents an impressive advancement, Clark, who was not involved in the research, noted that the technology in its current form cannot be used for fertility treatments due to the genetic abnormalities of the embryos.

“All the embryos were genetically abnormal. Therefore, this approach will not, and should not, be offered in the IVF lab until technical improvements are made,” Clark stated. Despite this, she acknowledged that millions of women suffering from primary ovarian insufficiency could benefit from future developments in this area.

The research utilized somatic cell nuclear transfer, a technique that gained fame with the cloning of Dolly the sheep in 1997. While this new study produced embryos with contributions from both parents, the connection to cloning raises regulatory concerns. Clark indicated that the regulatory barriers for clinical application will be significant.

Ying Cheong, a professor of reproductive medicine at the University of Southampton, described the breakthrough as an “exciting proof of concept.” She emphasized that while the research is still in its early stages, it has the potential to transform the understanding of infertility and miscarriage. “For the first time, scientists have shown that DNA from ordinary body cells can be placed into an egg, activated, and made to halve its chromosomes, mimicking the special steps that normally create eggs and sperm,” Cheong said.

As the scientific community reflects on these findings, the potential for future advancements in reproductive technology remains a topic of great interest and hope.