Natron Energy, a sodium-ion battery startup based in Santa Clara, California, ceased operations on September 3, 2023, primarily due to funding challenges. Just one year prior, Natron had ambitious plans to construct a US $1.4 billion manufacturing facility in North Carolina, aiming to produce up to 14 gigawatt-hours of sodium-ion batteries. While experts indicate that Natron’s closure does not necessarily foreshadow doom for the entire sodium-ion battery industry in the United States, they recognize that the U.S. lags behind China in battery manufacturing advancements.

K.M. Abraham, a retired research professor at Northeastern University and Chief Technology Officer of E-KEM Sciences, a lithium-ion battery consulting firm, highlights a key issue for U.S. sodium-ion startups like Natron, which launched in 2012. These companies often depend on the goodwill of investors, creating a precarious situation where funding timelines can exceed the pace of innovation. “Companies aren’t able to make progress quickly enough to keep up with pressure exerted by the investors,” Abraham states.

Natron’s Innovative Approach and Market Challenges

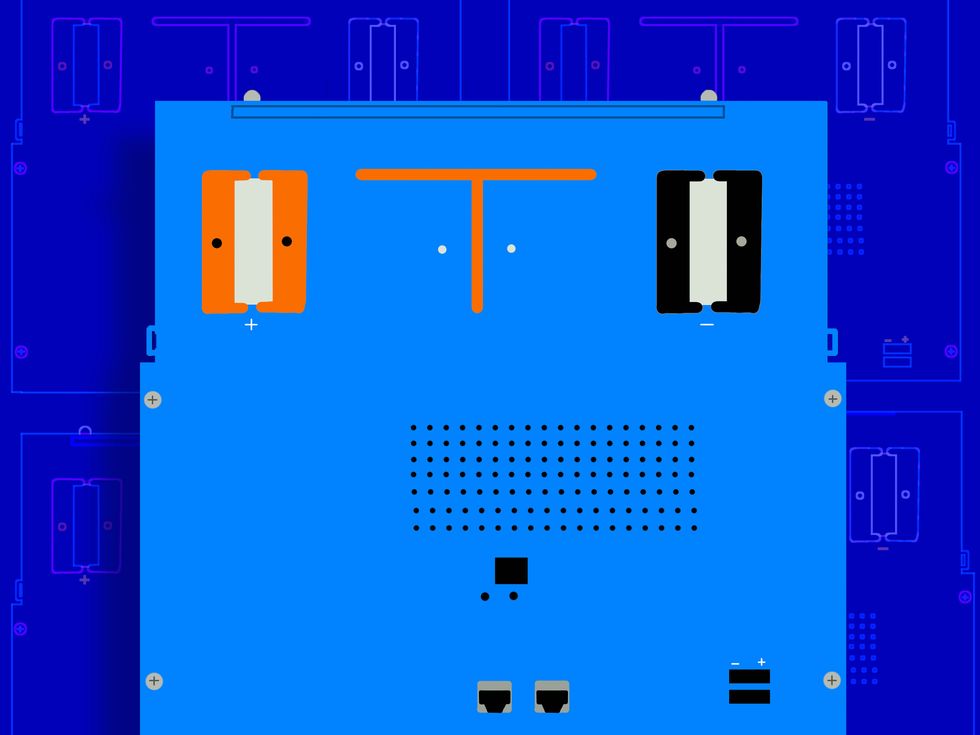

Until its recent shutdown, Natron was regarded as a frontrunner in the U.S. sodium-ion market, primarily due to its innovative use of Prussian Blue, a pigment commonly found in paints and dyes. This material was integral to the company’s battery systems, serving as both the cathode and anode. The low cost of Prussian Blue, alongside its chemical structure that facilitates rapid ion transfer, positioned Natron uniquely in a competitive market.

Tyler Evans, co-founder and CEO of Mana Battery, a Colorado-based sodium-ion battery startup, noted Natron’s achievement in commercializing a sodium-ion battery utilizing Prussian Blue. “They were doing it in the West, and they were scaling a technology that was relatively low energy density for a very specific market segment,” Evans remarked. This specific segment included applications such as grid storage and power backups for data centers, where safety and cost effectiveness often outweigh the need for high energy density.

Despite its potential, Natron encountered difficulties in scaling its operations. Evans emphasized the financial implications of producing batteries with low energy density, stating that manufacturers require more production lines to achieve the same output, leading to increased costs. “If you think about building a manufacturing facility where you want to produce 10 gigawatt-hours of batteries, if your energy density is very low, producing an equivalent number of batteries requires more manufacturing lines,” he explained.

In 2023, Natron’s systems reached the market, and the company partnered with Encorp to deploy a multi-megawatt power platform aimed at industrial applications. Following this, Natron opened the U.S.’s first commercial-scale manufacturing facility in Holland, Michigan, intended to supply energy storage for data centers. The U.S. Department of Energy’s ARPA-E program provided $19.8 million to support Natron’s transition from lithium-ion to sodium-ion manufacturing. This facility closed its doors concurrently with Natron’s headquarters in California.

A request for comment from Natron resulted in an automated reply directing inquiries to its primary shareholder, Sherwood Partners, which did not respond.

Industry Insights and Future Directions

Adrian Yao, founder of Stanford’s STEER initiative and author of a forthcoming paper comparing sodium-ion and lithium-ion batteries, commented on Natron’s technology, acknowledging its potential but suggesting the company may have misjudged the timing for its target market. “Hyperscalers right now, their primary concern is just getting connected and building data centers,” Yao observed, pointing to a possible mismatch in market readiness.

Natron’s closure follows that of Bedrock Materials, another sodium-ion startup that shut down in April 2023, citing market challenges. Andrew Thomas, president and co-founder of Acculon Energy, which specializes in sodium-ion cells for industrial applications, noted that the battery sector is notoriously difficult. He remarked, “There are a lot of tombstones” in this industry.

Compared to Natron, Acculon employs traditional layered-metal oxides, complicating comparisons across the sodium-ion landscape. “I don’t think one failure is representative of a country being unable, but we’re at a significant disadvantage given the installed base in China,” Thomas commented.

China continues to dominate the global battery market, producing more than 75 percent of the world’s batteries, according to the International Energy Agency. Companies like CATL are advancing sodium-ion technology, recently launching a second-generation battery geared toward electric vehicle applications.

Yao advocates for the U.S. to enhance its manufacturing capabilities to compete effectively with China. “My broader critique of the Western Hemisphere… is that we focus too much on tech,” he said, emphasizing the need for improved manufacturing processes and workforce training.

Despite the challenges, entrepreneurs like Evans and Thomas remain optimistic about the future of sodium-ion batteries. They believe that increasing demand for grid storage and cost-effective mobility solutions will drive interest in sodium-ion technology, which is well-suited for applications requiring safety and affordability.

Mana Battery is looking to emulate successful practices from China by forming partnerships with existing manufacturers to bolster production. Evans expressed confidence in the U.S. market’s readiness for such collaborations, indicating a potential path forward for sodium-ion technology in an evolving energy landscape.