A groundbreaking exploration in the 1240s by Dominican friar Richard Fishacre at Oxford University challenged the prevailing scientific beliefs of his time regarding the composition of stars and planets. Fishacre proposed that these celestial bodies were made of the same elements found on Earth, directly contradicting the widely accepted notion of the “fifth element” or quinta essentia, a concept rooted in the teachings of the ancient philosopher Aristotle.

Aristotle’s framework dictated that beyond the four earthly elements—fire, water, earth, and air—there existed a perfect, unchanging celestial element that composed the stars and planets. This “fifth element” was believed to form nine concentric spheres around the Earth, each containing a different celestial body. Fishacre, however, rejected this notion, asserting that the stars and planets were not composed of a distinct substance but rather of the same four elements present on Earth.

Fishacre’s Revolutionary Insight on Light and Color

Fishacre’s argument relied heavily on his understanding of light and color. He noted that color is typically associated with opaque bodies, which are made up of multiple terrestrial elements. Observations of celestial bodies revealed subtle colors; for instance, Mars appears red and Venus yellow. This evidence led him to conclude that these planets must be composed of the same four elements found on Earth, a position he articulated as “ex quattuor elementis,” or “out of the four elements.”

A pivotal point in Fishacre’s reasoning was the moon, which exhibited a distinct color and periodically eclipsed the sun. He argued that if the moon were made of the transparent fifth element, sunlight would pass through it as it does through glass. Its ability to block sunlight indicated that the moon, like Earth, shared a composition of terrestrial elements. If the moon could be established as such, then Fishacre posited that all celestial bodies must also share this elemental composition.

Facing Criticism and Historical Vindication

Fishacre’s revolutionary ideas were not without risks. He anticipated backlash from proponents of Aristotelian thought, acknowledging that his assertions would likely provoke criticism. He famously wrote, “If we posit this position, then they, that crowd of Aristotelian know-it-alls (scioli aristoteli), will cry out and stone us.” His fears were soon realized when, in 1250, his teachings were publicly denounced by St Bonaventure of Bagnoregio, a leading Franciscan friar who mocked those who questioned Aristotle’s teachings.

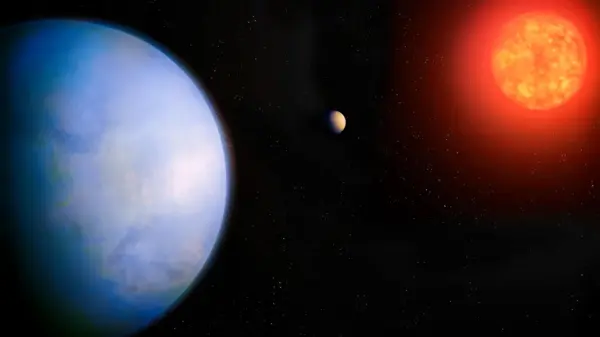

Despite the resistance he faced, modern astrophysics has since vindicated Fishacre’s claims. Contemporary research demonstrates that the stars and planets are not made of a unique fifth element. Instead, they consist of many of the same elements and metals found on Earth. For instance, the James Webb Space Telescope recently identified significant quantities of water and sulfur dioxide in the atmosphere of the exoplanet TOI-421 b, located approximately 244 light years from Earth.

Remarkably, the method employed by the James Webb Space Telescope—known as transmission spectroscopy—bears a resemblance to Fishacre’s approach. This technique detects subtle variations in the brightness and color of emitted light, which can be attributed to specific substances, such as water and sulfur dioxide.

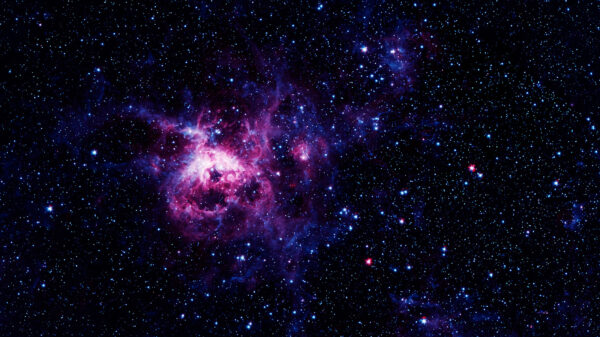

Fishacre’s legacy endures, illustrating the timeless nature of scientific inquiry and the pursuit of knowledge. Nearly 800 years after his death, modern astronomy continues to utilize light and color to reveal the elemental makeup of distant stars and planets, reaffirming Fishacre’s pioneering insights in the realm of celestial science.