UPDATE: Tensions escalate in Owens Valley as groundwater pumping by Los Angeles continues to draw criticism from Indigenous tribes seeking restitution of their water rights. Just moments ago, tribal leaders voiced urgent concerns about the drastic environmental impacts caused by L.A.’s extensive water extraction operations.

In the heart of the Owens Valley, California, a stark reality unfolds. A single well among the 105 owned by Los Angeles pumps water into a canal, feeding into a desert landscape that has suffered from decades of water deprivation. Local Indigenous leaders assert that these actions are leaving their ancestral lands parched and damaging vital ecosystems. “We’ve seen so many impacts from groundwater pumping,” stated Teri Red Owl, an executive director of the Owens Valley Indian Water Commission.

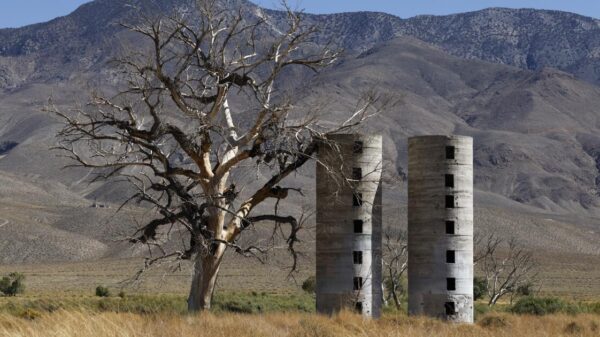

This urgent situation is compounded by a historical backdrop; L.A. has been extracting water from the Owens Valley since the early 1900s, a practice that has transformed once-lush wetlands into barren landscapes. Tribal members, part of the Bishop Paiute Tribe, describe their homeland as Payahuunadü—“the land of flowing water”—now stripped of its lifeblood. Red Owl emphasizes that the city’s actions have drained vital “life force” from their territory, pushing them to demand a reduction in L.A.’s water extraction.

In a critical letter this summer, a coalition of 30 professors and researchers urged L.A. Mayor Karen Bass to reopen negotiations with the three affected tribes, advocating for essential water and land rights. “It is time to listen to what the Tribes are asking for,” they wrote, underscoring the urgency of the situation.

Los Angeles officials, however, maintain that groundwater is being managed sustainably. Adam Perez, director of water operations at the L.A. Department of Water and Power (DWP), insists that the city is drawing significantly less water than it did in the 1970s, following a landmark agreement with Inyo County in 1991. DWP plans to pump between 62,000 and 83,000 acre-feet of groundwater this year, about 12% to 16% of Los Angeles’s annual consumption. Yet, tribal leaders argue that this volume continues to deplete a critical aquifer beneath their homeland.

The fallout from this water extraction is starkly visible. Noah Williams, a member of the Bishop Paiute Tribe, recalls the vibrant springs that once flourished where he stands today, now a parched desert. “This is a man-made drought,” he asserts, pointing to ancient sites where water once thrived. The loss of these water sources has not only affected wildlife but has also stripped the tribes of traditional practices, leaving them bereft of the resources they once relied upon.

Environmental advocates echo these sentiments, criticizing DWP’s restoration efforts as inadequate. Lynn Boulton, local conservation chair for the Sierra Club, laments the loss of riparian habitats and invasive species that have taken over once-thriving ecosystems. She insists that reducing L.A.’s groundwater pumping is essential for reviving the valley’s health.

Despite ongoing environmental restoration projects, tribal leaders assert that these initiatives do not compensate for the loss of their water rights. Under current agreements, they remain without legal recognition of their claims to water, even as the Bureau of Indian Affairs assesses their situation.

The urgency of this matter cannot be overstated. A community of Indigenous people is caught in a struggle for survival against a powerful city that continues to consume their natural resources. The message from tribal leaders is clear: without immediate action, the future of their homeland hangs in the balance. “I feel like they’re taking everything they can, every single drop,” warns Thomas River Watterson, a member of the Bishop Paiute Tribe, highlighting the dire consequences of continued over-extraction.

As negotiations loom, the calls for justice and restoration grow louder. The tribes demand recognition and rights to restore their lands and water. The world will be watching as this urgent situation develops, hoping for a resolution that honors both the environment and the Indigenous communities that have cared for it for generations.