URGENT UPDATE: New evidence has emerged revealing that Neolithic communities in northeastern France engaged in brutal warfare, including the mutilation of prisoners of war. A study published today in Science Advances uncovers shocking findings that could redefine our understanding of violence during this period.

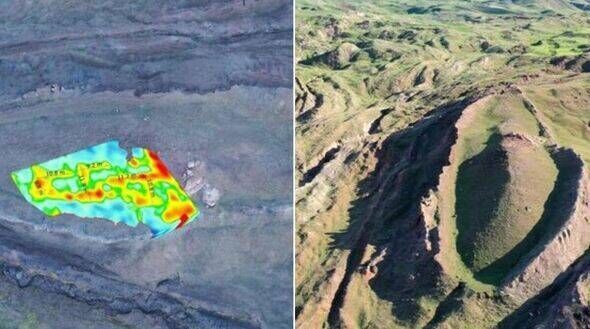

Researchers from an international team analyzed skeletal remains from burial pits dating back to between 4300 and 4150 BCE near Strasbourg, specifically in the sites of Achenheim and Bergheim. They examined a total of 82 human remains, some of which displayed horrific wounds indicative of violent deaths.

The study highlights significant differences between the victims and non-victims, suggesting that the former were likely members of invading groups who faced gruesome ends at the hands of local populations. The researchers described these findings as potentially some of the earliest documented instances of victory celebrations related to warfare in prehistoric Europe.

“Some remains bore gruesome wounds,” the study states. It details that individuals who suffered from severe injuries, including unhealed skull fractures, were likely victims of war violence, contrasting sharply with those who received regular burials.

To determine the origins of these individuals, lead researcher Teresa Fernandez-Crespo from Valladolid University conducted isotopic analyses on the remains. This research revealed that while non-victims were identified as locals, the victims originated from other regions, supporting the theory that they were invaders killed during conflicts.

“We can attribute the identities of these victims to socially remote, nonlocal enemies that became trophies or captives during battles or raids,” the researchers stated. This brutal treatment suggests a dehumanizing perspective towards these invaders, reinforcing the concept of warfare in Neolithic society.

The implications of this study are profound, as they suggest that warfare and its associated rituals were prevalent much earlier than previously believed. This new understanding not only sheds light on the violent practices of our ancestors but also raises questions about the social dynamics and cultural tensions present in prehistoric Europe.

As this research continues to gain attention, it invites further investigation into the nature of violence and warfare in ancient societies. The findings are expected to prompt rigorous discussions among historians and archaeologists about the evolution of conflict and human behavior.

Stay tuned for more updates and in-depth analyses as this story develops.