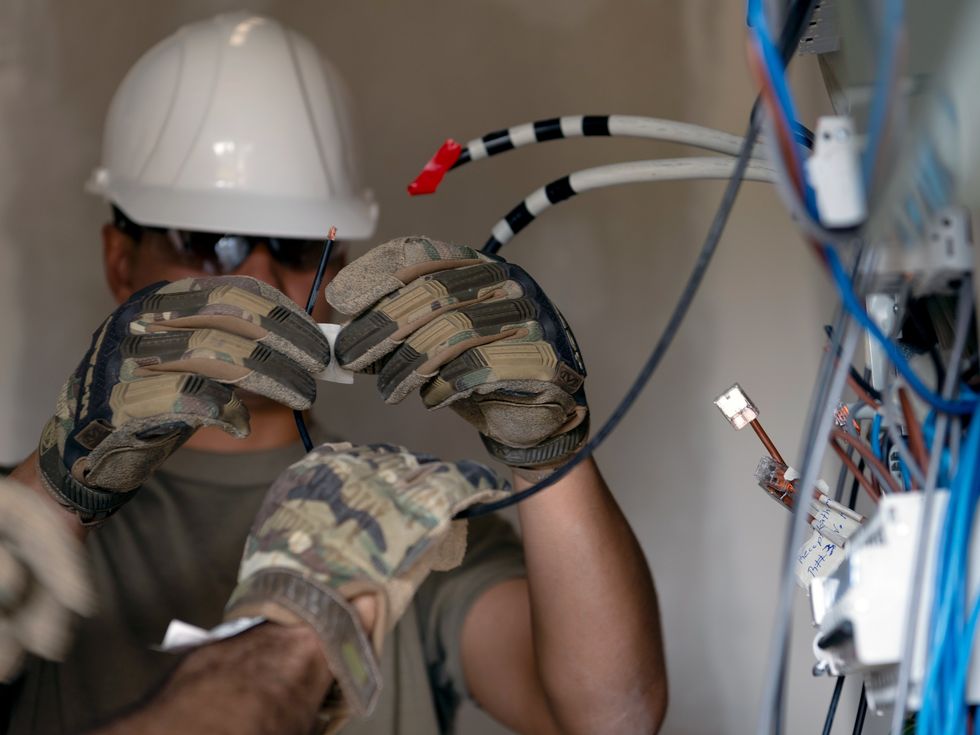

The energy sector is facing a significant challenge as a shortage of skilled engineers threatens to disrupt the future of power infrastructure. According to a joint study conducted by consulting firm Kearney and the IEEE, the global power industry will require between 450,000 and 1.5 million additional engineers by 2030. This urgent demand comes at a time when renewable energy sources are expanding and data centers are consuming more electricity than ever.

A gap in skilled talent is already visible, with approximately 40 percent of power executives indicating difficulty in hiring qualified workers. They cite intense competition for talent and a lack of necessary skills as primary obstacles. This workforce crisis is particularly concerning for energy leaders, who warn that it could delay essential upgrades to the power grid at a moment when rapid evolution is crucial.

Impact of the Engineer Shortage

The implications of this talent shortage are profound. With extreme weather events increasingly straining aging equipment, the potential for more frequent service disruptions looms large. Furthermore, hiring challenges could hinder timelines for integrating clean energy solutions, expanding transmission networks, and maintaining nuclear facilities, thereby jeopardizing both reliability and the pace of decarbonization efforts.

Andre Begosso, a partner at Kearney, explained to IEEE Spectrum that “without enough engineers, these critical projects will be delayed, compounding reliability risks and slowing the energy transition at the exact moment when momentum is needed most.”

The causes of the engineering shortage are multi-faceted. An aging workforce, particularly among baby boomers, is retiring without a sufficient influx of younger professionals to take their place. “Utility companies are facing a perfect storm of a labor crisis,” noted Kevin Miller, North America’s chief technology officer at IFS, a software company serving the energy sector.

Challenging working conditions also contribute to the exodus of engineers from the field. In the past three years, nearly half of all power engineers have either changed jobs or left the industry entirely, with burnout and a lack of creative problem-solving opportunities cited as significant reasons for this turnover. In the nuclear sector, the situation is even more dire, with 58 percent of engineers changing roles.

Addressing the Talent Gap

The education pipeline for future engineers is also drying up. Enrollment in power engineering programs has stagnated as students gravitate towards high-tech fields such as data science and AI, which are perceived as more dynamic and lucrative. Even when companies are able to recruit new talent, the onboarding process is often slower than in other sectors. Miller explained that lengthy hiring processes and extensive training cycles can extend timelines and divert supervisors from core operations.

At Black & Veatch, a major engineering firm in the United States, early-career recruitment is essential for addressing staffing shortages. The firm has been successful in converting 85 to 90 percent of its interns into full-time hires, achieving a remarkable 93 percent conversion rate last summer. Despite these efforts, the firm still faces challenges at the experienced level. “Hiring top-tier seasoned engineers is really no small feat,” said Ryan Elbert, executive vice president and global director of engineering and development services at Black & Veatch.

Smaller firms are particularly vulnerable in this competitive landscape. With fewer resources, they often struggle to compete with larger companies that can offer superior salaries and benefits. Heather Eason, CEO of Select Power Systems, described how a junior engineer hired right out of college was lured away by a competitor for just $5 more an hour. For many younger workers, “money speaks,” Eason observed.

Moreover, the process to become a licensed professional engineer can deter potential candidates. This requires a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering, completion of the Engineer-in-Training (EIT) and Professional Engineering (PE) exams, and four years of work experience. Although these certifications are not mandatory for employment, they enhance job prospects and potential earnings. Eason pointed out that the lengthy process can be particularly challenging for women who may have additional caregiving responsibilities.

To combat the skills shortage, some utilities are leveraging technology to maximize the productivity of their existing workforce. For instance, IFS utilizes augmented reality tools that enable experienced technicians to guide less experienced colleagues in real-time troubleshooting.

Upskilling initiatives are gaining traction as companies seek to enhance their workforce. At the Power Academy, a training program run by global engineering firm TRC Companies, demand from utilities and data centers is rapidly increasing. Director of technical services Anna Campbell noted that clients require specialized skills in protection, controls, and substation engineering, which are integral to the program.

In the United Kingdom, Excitation & Engineering Services (EES) has adapted its graduate recruitment strategy to ensure that young engineers work alongside experienced professionals from the outset. “It shortens the learning curve but, most importantly, it passes on that knowledge from senior engineers while it’s still available,” said EES director Ryan Kavanagh.

Meanwhile, educational initiatives such as those offered by Bentley Systems aim to equip university students with essential skills through free access to engineering software and online courses. Chief sustainability and education officer Chris Bradshaw remarked, “The more we can embed innovation deeper into education, the faster we can deliver on sustainable, resilient infrastructure projects.”

As the industry grapples with this pressing talent shortage, timely action is crucial. If the skills gap remains unaddressed, the energy sector’s ability to innovate and maintain reliability will be severely hampered, impacting both economic competitiveness and sustainable energy futures. Begosso concluded, “The strength of the energy workforce will go a long way in determining how competitive and reliable the power sector, and the economy it underpins, can be in the next decade.”