The ambitious vision of vast cities in space, once championed by physicist Gerard K. O’Neill, has yet to materialize as humanity grapples with the realities of space exploration. In the 1970s, O’Neill envisioned self-sufficient habitats populated by millions, looking down from their orbital vantage points. Today, in 2025, only a select few astronauts have experienced life beyond Earth, with the International Space Station hosting just 290 individuals thus far.

O’Neill captured the imagination of the public with his best-selling book, “The High Frontier,” published in 1976. He argued for the construction of grand space habitats at the L5 Lagrange Point, where conditions would allow for communities of millions. His ideas gained significant traction, leading to the establishment of the L5 Society, which adopted the slogan, “L5 by ’95!”

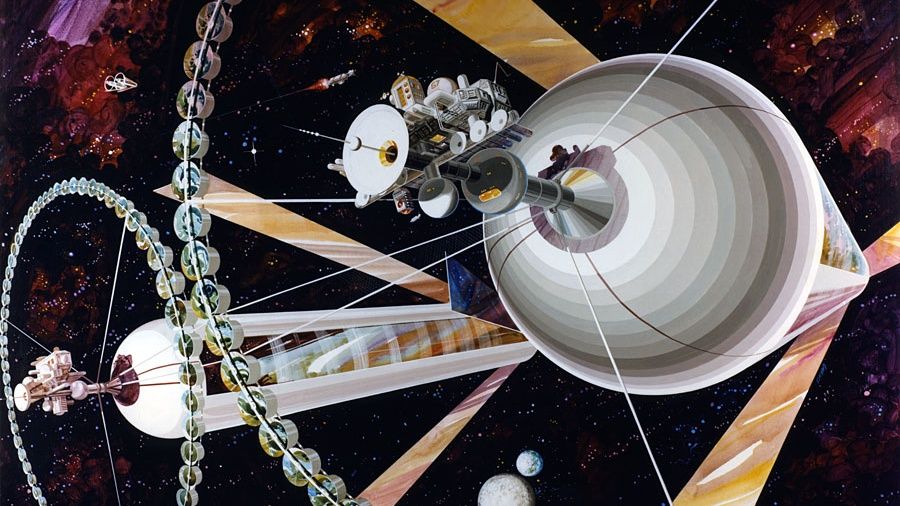

In his vision, cylindrical habitats would utilize rotation to create a centrifugal force simulating gravity. O’Neill proposed various designs, including his largest model, known as Island Three, which would stretch four miles (6.4 kilometers) wide and 20 miles (32 kilometers) long, offering 500 square miles (1,294 square kilometers) of living space. These habitats would feature homes, parks, and recreational areas, akin to the fictional worlds portrayed in science fiction.

Despite the excitement surrounding O’Neill’s ideas, the reality of space habitation has proven far more complex. He posited that the raw materials needed for construction could be mined from the moon and asteroids, transported via a technology called a mass driver. This electromagnetic system would propel payloads into space, allowing for continuous launches without the need for traditional fuel sources.

O’Neill’s optimism about the technological feasibility of building these habitats was not unfounded. The 1970s had ushered in many advancements that seemed to support his claims. Yet, his projections have not come to fruition. The International Space Station has been the pinnacle of human achievement in space, with the technologies needed for O’Neill’s grand habitats still untested as of today.

A significant setback to O’Neill’s vision was the failure of the space shuttle program. Initially designed for hundreds of launches per year, the fleet managed only 135 flights from its inaugural launch in 1981 to its retirement in 2011. Without the expected infrastructure to support space mining and habitation, the dream of living in space remained just that—a dream.

O’Neill estimated the cost of constructing a 20-mile-long habitat at around $200 billion in 1970s currency, translating to approximately $1.1 trillion today. This financial barrier, combined with social challenges, raises critical questions about equity in access to space. If the goal is to alleviate Earth’s overpopulation, relocating millions to space seems insufficient given the planet’s current population of over 8 billion.

The notion of who would inhabit these space cities also poses ethical dilemmas. History suggests that opportunities for living in space could favor the wealthy, further widening the gap between rich and developing nations. The logistics of ensuring equitable access to space habitats may prove to be as challenging as the engineering required to construct them.

Despite these obstacles, O’Neill’s vision serves as a poignant reminder of humanity’s potential. His ideas reflect a time when space exploration was synonymous with hope and progress. The realities of the 21st century, marked by conflict, environmental degradation, and social inequality, prompt reflection on what has been lost since those optimistic days.

As humanity stands at a crossroads, the dreams of space cities may not be entirely extinguished, but they are tempered by the complexities of real-world challenges. O’Neill’s legacy invites us to consider not only the technical aspects of space habitation but also the broader implications for society as we venture into the cosmos.