A recent study conducted by the Complexity Science Hub in collaboration with TU Graz has unveiled how individuals belonging to multiple marginalized groups face compounded challenges in forming social connections. Published in Science Advances, the research highlights that social isolation does not merely accumulate; rather, it can intensify when various forms of discrimination intersect.

The study addresses a critical question: why do some individuals enjoy a wealth of friendships and support, while others experience a stark lack thereof? Researchers suggest that the issue extends beyond personal choices, indicating deeper structural patterns at play. Individuals from disadvantaged social groups frequently find it difficult to establish connections. This struggle intensifies for those belonging to multiple marginalized categories, such as women from migrant backgrounds living in poverty.

Study author Samuel Martin-Gutierrez explains, “Disadvantages can amplify one another when they intersect.” To investigate this phenomenon, the researchers developed a mathematical model and analyzed friendship data from approximately 40,000 U.S. high school students from the academic years 1994/95.

Understanding Social Networks

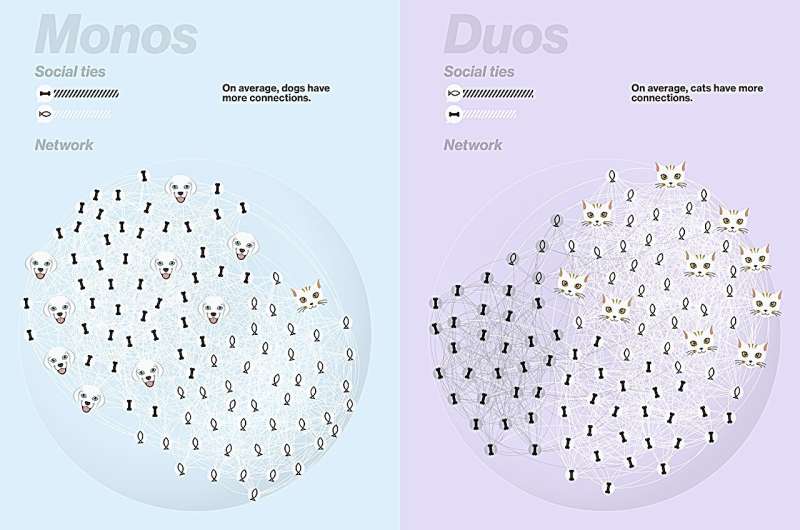

Social networks are not formed randomly; they are influenced by factors such as gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic background. The tendency for individuals to connect with those who share similar traits is known as homophily. This inclination means that certain groups forge stronger ties within their communities and access central parts of social networks, leading to greater opportunities for support and information.

In contrast, marginalized groups often find themselves on the fringes of these networks. They possess fewer connections to influential social circles and tend to connect with others who are similarly isolated. This structural disadvantage limits access to vital opportunities, including educational and job prospects. Martin-Gutierrez notes, “When majority groups mostly connect among themselves, it creates a kind of structural invisibility for minorities.”

The Impact of Intersectional Inequalities

The study sheds light on the experiences of individuals who occupy multiple marginalized identities. For instance, women with a migrant background from low-income families encounter challenges that do not simply add up; rather, they can result in intensified disadvantages in unexpected ways. Martin-Gutierrez emphasizes that intersectional inequalities have not received adequate attention in previous research.

The researchers’ findings reveal that overlapping disadvantages manifest in complex and often surprising patterns. For example, while girls generally have more friends than boys, Black girls and Asian boys represent exceptions, having fewer connections than their male counterparts. This dynamic illustrates how the structural disadvantages of being both Black and female can outweigh the broader trend favoring female friendships.

The mathematical model developed for this study accurately predicted friendship patterns with a remarkable 92% accuracy, demonstrating the potential for understanding social networks through an intersectional lens.

In conclusion, the insights gained from this research can inform the design of educational institutions, social platforms, and policy initiatives aimed at addressing structural disadvantages. By recognizing the complexities of individual identities, stakeholders can better identify systemic issues and work to foster more inclusive environments.

For further exploration of social fairness and its implications, readers can engage with an interactive visualization created by the researchers, which allows users to experiment with factors affecting social connections in a fictional setting.

The comprehensive approach taken in this study underscores the importance of viewing individuals in their full complexity, paving the way for more effective interventions that promote social equity.