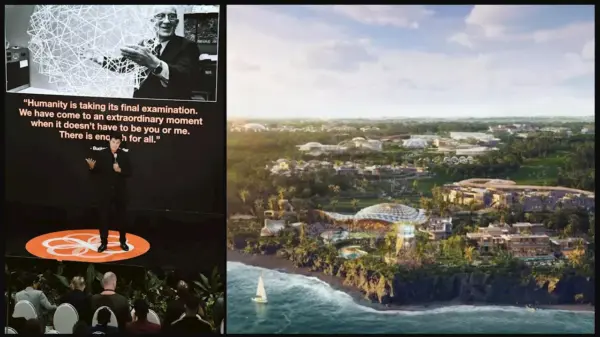

The ambitious pursuit of establishing data centers in space is encountering significant challenges rooted in the laws of physics and economics. As major tech companies like Microsoft, Google, and Amazon grapple with increasing energy demands to power their artificial intelligence operations, the idea of relocating cloud computing to orbit has gained traction. The European Commission’s recent study, the ASCEND (Advanced Space Cloud for European Net Zero Emission and Data Sovereignty), led by Thales Alenia Space, explored this concept. While the study concluded that placing data centers in orbit is technically feasible, it also underscored formidable engineering challenges that could undermine the financial viability of such projects.

The ASCEND feasibility study, which included contributions from leading firms such as Airbus and ArianeGroup, aimed to assess whether orbital data centers could significantly reduce the carbon emissions associated with digital infrastructure. Although the findings suggested a potential pathway, experts cautioned that the realities of thermodynamics present significant obstacles. The promise of unlimited solar energy and cooling in the vacuum of space is tempered by the harsh truths of thermal management and the complexities of launch logistics.

Thermodynamics and the Reality of Cooling in Space

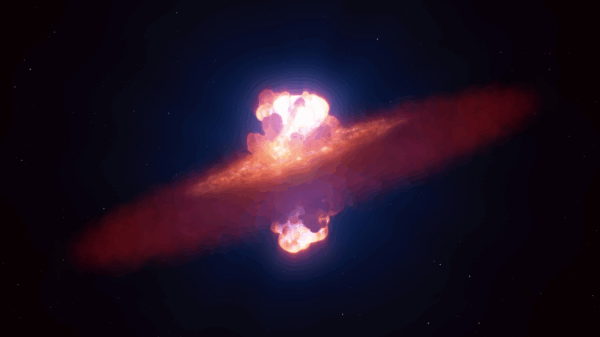

Proponents of space-based data centers often cite the concept of “free cooling,” suggesting that the frigid environment of space could substantially lower energy costs. Yet, a detailed analysis by Taranis.ie reveals a critical misunderstanding of heat transfer in a vacuum. Unlike Earth, where air convection cools servers, space relies solely on radiation, which is considerably less efficient. This means that to effectively dissipate heat generated by high-performance chips, an orbital facility would require extensive radiator panels, far exceeding the size of solar arrays needed for power generation.

The engineering hurdles do not stop at thermal management. In the unforgiving environment of low Earth orbit (LEO), high-energy particles and cosmic radiation pose additional risks to hardware longevity. While Microsoft Azure Space has successfully tested commercial servers on the International Space Station (ISS), adapting technology for sustained operation in orbit remains prohibitively expensive. Unlike terrestrial data centers, where technicians can swiftly replace malfunctioning components, orbital hardware failures result in irretrievable losses.

Economic Viability: Launch Costs and Maintenance Challenges

The financial feasibility of space-based data centers hinges on the expectation of reduced launch costs, particularly with innovations like SpaceX’s Starship. Even if the cost of launching payloads drops to $100 per kilogram, the overall cost of ownership presents significant challenges. The lack of maintenance capabilities in orbit means that a single failure could lead to substantial downtime. To achieve reliability levels comparable to Earth-based systems, operators would need to launch excess capacity, drastically increasing the amount of hardware in orbit.

Startups such as Lumen Orbit, backed by Y Combinator, believe that the demand for in-orbit processing could justify these costs. Their focus is on “edge computing” where data generated by satellites—covering vast amounts of imagery and signals intelligence—can be processed near the source, thus alleviating bandwidth constraints. However, this approach may not extend to broader applications, such as streaming services or financial transactions, where latency issues become pronounced.

The Wall Street Journal previously reported on the collaboration between Microsoft and SpaceX to integrate Azure with the Starlink satellite network. The primary aim of this partnership is to enhance reach rather than replace existing terrestrial facilities, reinforcing the notion that the cloud will likely remain grounded for the foreseeable future.

Legal and Environmental Concerns

Beyond the technical and financial hurdles, the legal implications of operating orbital data centers present a complex challenge. Data sovereignty laws, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union, impose strict requirements on the physical location of data storage. The legal status of servers in orbit, which constantly traverse international borders, remains ambiguous. This uncertainty complicates compliance for enterprise clients that require stringent data management practices.

Environmental concerns also loom large. Research published in Earth’s Future suggests that emissions from frequent rocket launches could negate any potential carbon savings achieved by solar power in space. If the industry were to scale up to replace even a fraction of terrestrial capacity, the environmental impact could be significant, casting doubt on the sustainability of these ambitious plans.

As the sector navigates these challenges, the vision of large-scale orbital data centers may be tempered. While there is increasing investment and interest, particularly from national governments viewing space infrastructure as strategic assets, the reality is likely to be a more modest integration of space-based computing as specialized edge nodes. The current phase of “irrational exuberance” in the industry, driven by decreasing access costs to space, may give way to a more pragmatic approach as the implications of thermodynamics and engineering realities become clearer.

Ultimately, despite the allure of orbital computing, the fundamental laws of physics remain unchanged, and the dream of floating data centers may remain just that—a dream.