A team of researchers has revealed a groundbreaking method used by bacteria to navigate through minuscule passages that are only slightly larger than their own bodies. By wrapping their flagella around themselves, these microorganisms can move effectively through 1-micrometer-wide tunnels, as detailed in a study published on January 25, 2026, in Nature Communications.

Led by Dr. Daisuke Nakane and Dr. Tetsuo Kan from the University of Electro-Communications in Japan, along with Dr. Hirofumi Wada from Ritsumeikan University and Dr. Yoshitomo Kikuchi from the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, the research highlights a unique “flagellar wrapping” motion that allows symbiotic bacteria, such as Caballeronia insecticola, to advance through narrow anatomical structures typically found in insect guts.

Innovative Movement Mechanism

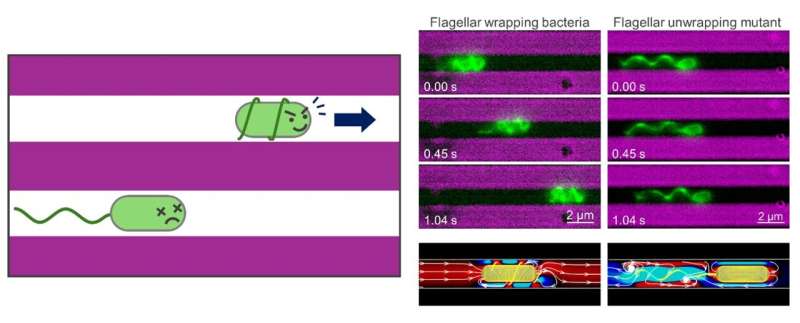

In their study, researchers utilized a specially designed microfluidic device that mimics the environment of insect gut channels. This setup revealed how bacteria wrap their rotating flagella—helical structures used for propulsion—around their cell bodies, forming a screw-like mechanism that helps them move forward. Under microscopic examination, Caballeronia insecticola was observed skillfully maneuvering through the narrow channels by continuously wrapping and unwrapping its flagella. In contrast, related species that lacked this ability remained immobilized.

Computer simulations further validated the advantages of the wrapping technique. In confined spaces, traditional flagellar rotation merely stirs the surrounding fluid, while the wrapping mode produces a more effective propulsion akin to a corkscrew, enabling the bacteria to push themselves forward efficiently. The researchers identified a flexible joint known as the hook, which connects the flagellar motor to its filament, as essential for this movement. Genetic experiments demonstrated that transferring hook genes from a wrapping species to a non-wrapping counterpart negated the latter’s ability to navigate confined spaces and infect host insects.

Broader Implications

This discovery not only sheds light on bacterial movement but also offers insights into potential applications in biology and engineering. Understanding how these microorganisms exploit mechanical principles to traverse complex environments could inspire the development of microrobots capable of navigating challenging settings, such as human tissues or complex filtration systems.

Dr. Nakane emphasized the significance of this finding, stating, “Flagellar wrapping shows how life solves mechanical problems in elegant, unexpected ways. It’s a microscopic version of engineering ingenuity, evolved by nature itself.” The study by Aoba Yoshioka et al. marks a significant advancement in microbiological research, opening new avenues for exploration in both natural and applied sciences.