A recent study led by Dwight Bergles at Johns Hopkins Medicine has uncovered significant insights into the differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), which may pave the way for new treatments for multiple sclerosis (MS). This autoimmune disease, characterized by the degradation of myelin in the central nervous system, presents substantial challenges in developing effective therapies. The findings, published in the journal Science, delve into how OPCs contribute to myelin repair and highlight potential new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

The research team employed a multifaceted approach to investigate how OPCs differentiate into mature oligodendrocytes. They utilized gene expression analysis across multiple species, including mice, marmosets, and humans, along with protein localization studies in brain tissue and time-lapse microscopy in live mice. This comprehensive methodology allowed the researchers to gain a clearer understanding of the differentiation process. Bergles noted, “This multifaceted approach gives us greater confidence in the conclusions, as it did not depend on one method alone.”

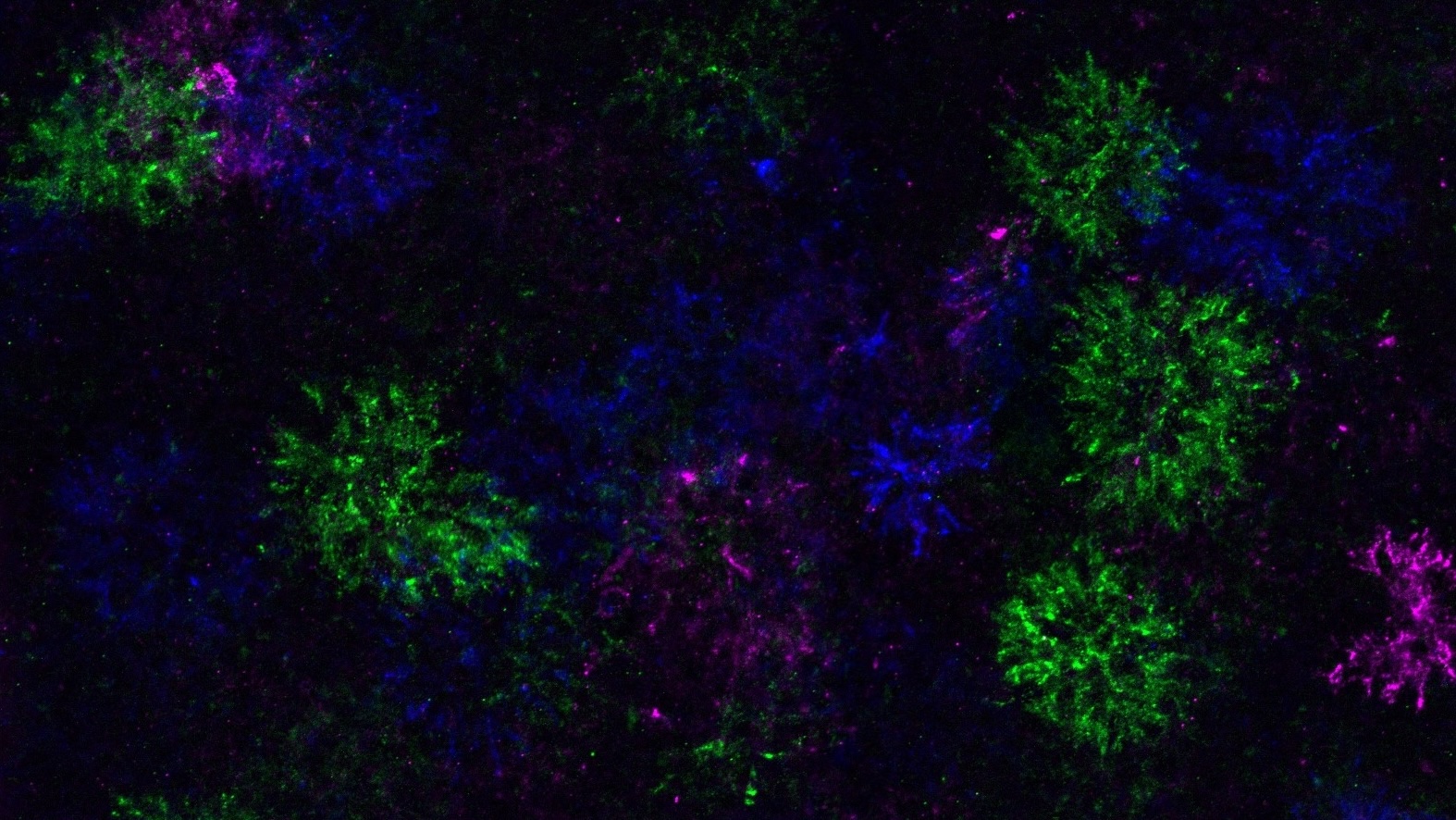

During the differentiation process, OPCs not only alter their own gene expression but also modify the surrounding extracellular matrix. This leads to the formation of unique structures referred to as “dandelion clock-like structures” or DACS. Bergles explained, “This understanding gives us a new way to study where and when this happens in the brain, a question that was not possible to answer before.” The ability to track these changes in real-time within live mice has provided valuable insights into the dynamics of OPC differentiation.

Interestingly, the research team discovered that OPCs attempt to differentiate throughout the brain, even in regions where they cannot form oligodendrocytes. This suggests that the differentiation process is primarily regulated by the OPCs themselves, rather than being driven by external factors such as the loss of existing oligodendrocytes. To further explore the influence of disease and aging, the team simulated myelin-related disorders by removing oligodendrocytes and myelin from mouse brains. They found that neither the rate nor the location of OPC differentiation changed significantly in these models.

Bergles emphasized the implications of these findings, stating, “We often talk about myelin ‘regeneration’ or ‘repair,’ but our studies suggest that what happens is simply a continuation of developmental myelination.” This raises important questions about the lack of a targeted regenerative mechanism for myelin in the brain. The study also indicated that the rate of OPC differentiation diminishes with age, potentially contributing to increased disability in individuals with MS as they grow older.

The research has filled a substantial gap in understanding the function and development of OPCs. Yet, Bergles acknowledged that many questions remain unanswered. “We are excited about exploring why OPCs change the surrounding extracellular matrix just when they start to differentiate,” he stated. The team plans to investigate the mechanisms behind this early differentiation, as well as the survival of newly differentiated oligodendrocytes in regions where they do not fully mature.

Bergles asserted the importance of collaborative efforts in scientific research, highlighting that diverse perspectives can lead to unexpected insights. “Science is a team effort, and this project exemplifies how diverse perspectives can lead to unexpected new insights about brain development and repair.”

As research continues, the implications for treating neurodegenerative diseases like MS remain promising. By understanding the underlying mechanisms of oligodendrocyte differentiation, researchers hope to develop more effective strategies for restoring myelin integrity in affected patients.