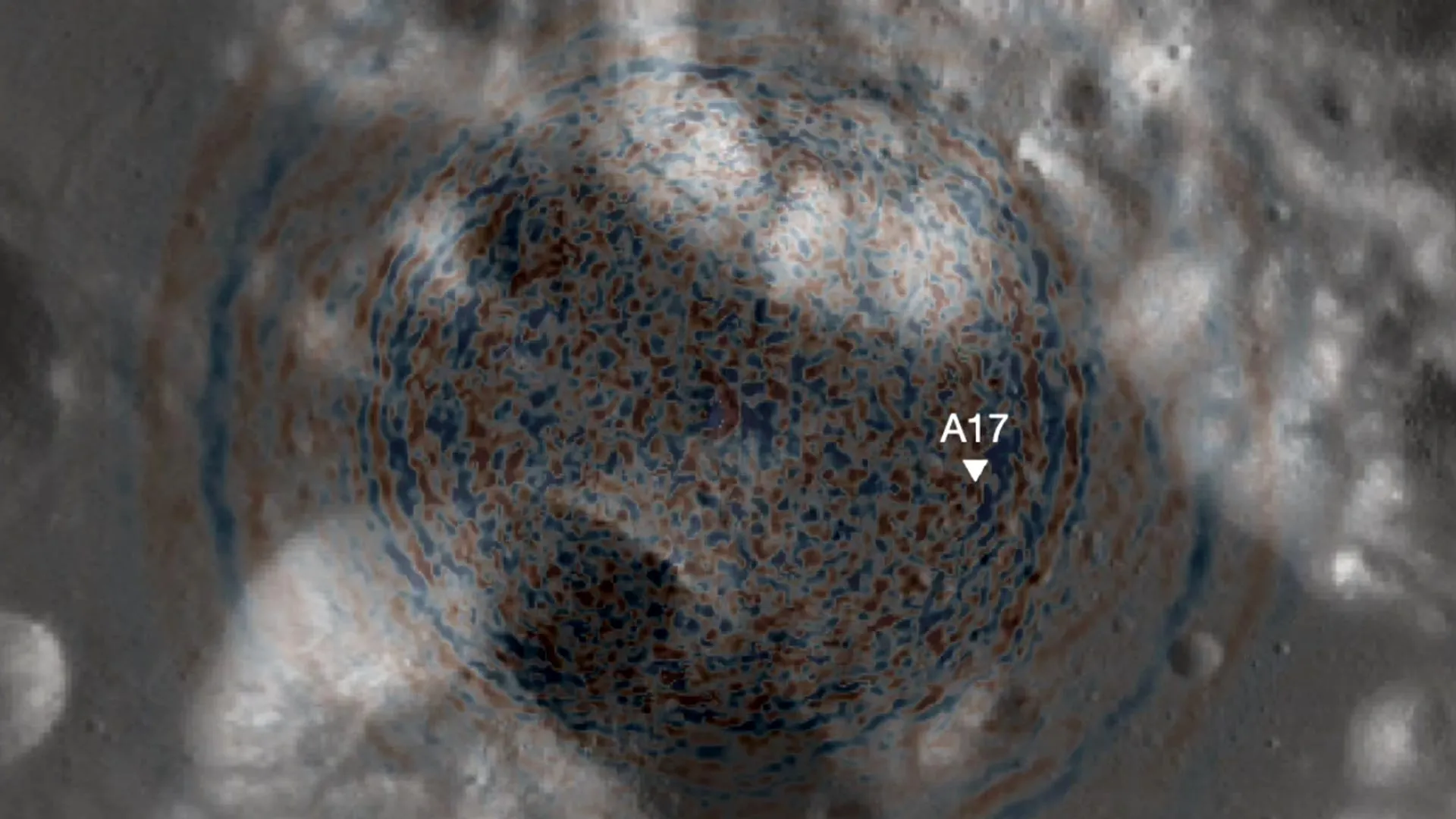

Scientists have discovered that moonquakes, rather than meteoroid impacts, are responsible for shifting terrains near the Apollo 17 landing site, as detailed in a study published on December 7, 2025, in the journal Science Advances. This revelation comes from researchers at the University of Maryland, who have identified a previously active fault that has been generating quakes for millions of years. The findings have significant implications for future lunar missions and the establishment of long-term bases on the Moon.

The research team, composed of Smithsonian Senior Scientist Emeritus Thomas R. Watters and University of Maryland Associate Professor of Geology Nicholas Schmerr, used geological evidence collected during the Apollo 17 mission to examine the Taurus-Littrow valley. This site, where astronauts landed in 1972, has shown signs of ground movement attributed to moonquakes. Their analysis indicates that these seismic events, with magnitudes near 3.0, have repeatedly affected the area over the last 90 million years.

Understanding Moonquake Activity

Watters and Schmerr’s investigation revealed that surface features, such as boulder tracks and landslides, have been mobilized by seismic activity. Because the Moon lacks the robust seismic monitoring instruments available on Earth, the researchers relied on geological indicators to estimate the strength of past quakes. Schmerr explained, “We had to look for other ways to evaluate how much ground motion there may have been.”

The study highlights the Lee-Lincoln fault, a tectonic feature that intersects the valley floor. The fault appears to be one of several young thrust faults on the Moon that may still be active. Watters emphasized the importance of considering such faults when planning for lunar infrastructure, stating that their potential for ongoing activity must be factored into the location and stability assessments of future lunar outposts.

Evaluating Risks for Long-term Lunar Missions

The researchers also calculated the daily probability of experiencing a damaging quake near an active fault. Their findings suggest a one in 20 million chance of such an event occurring on any given day. While this may seem minimal, Schmerr cautioned that the risk cannot be overlooked, especially for missions involving extended stays.

Short-duration missions, like Apollo 17, face little danger, but long-term projects will encounter a growing risk of seismic events. Upcoming missions, particularly those utilizing taller lander designs, could be more vulnerable to ground acceleration due to moonquakes. As NASA advances the Artemis program, which aims to establish a continuous human presence on the Moon, these considerations become increasingly critical.

Schmerr pointed out that the risk of a hazardous moonquake could rise significantly for missions lasting years. “If you have a habitat or crewed mission up on the Moon for a whole decade, that’s 3,650 days times one in 20 million, or the risk of a hazardous moonquake becoming about one in 5,500,” he explained. This comparison highlights the importance of carefully assessing seismic risks when planning for lunar habitats.

The research contributes to the evolving field of lunar paleoseismology, which focuses on ancient seismic activity on the Moon. Unlike Earth, where scientists can excavate to gather evidence of past earthquakes, lunar researchers rely on existing material and orbital imaging. Future advancements in technology and higher resolution mapping are expected to enhance understanding in this field.

Future Directions and Safety Measures

Watters and Schmerr emphasized the need for modern missions to incorporate safety measures that were not considered during the Apollo era. They advise future mission planners to avoid constructing facilities directly atop scarps or active faults. “The farther away from a scarp, the lesser the hazard,” Watters stated.

This research was supported by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission, which has been operational since its launch on June 18, 2009. While the findings provide critical insights, they underscore the necessity of prioritizing safety and informed decision-making for lunar exploration.

As NASA continues its work on the Artemis program and prepares for future lunar missions, the implications of these discoveries will play a vital role in shaping the plans for human exploration of the Moon. The study serves as a reminder that while the Moon may seem distant and stable, it harbors dynamic geological processes that must be carefully considered in the quest for sustained human presence beyond Earth.