A recent study conducted by an international research team has uncovered significant fossil evidence from the Permian Period, enhancing our understanding of life before the catastrophic Great Dying event. Over 17 years, researchers collected fossils from various sites in Tanzania and Zambia, revealing a diverse array of species that thrived in these regions around 252 million years ago.

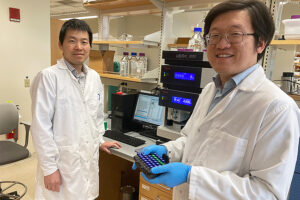

Christian Sidor, a professor of biology at the University of Washington and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the UW Burke Museum, emphasized the importance of this research. “This mass extinction was nothing short of a cataclysm for life on Earth and changed the course of evolution,” Sidor stated. He noted the need for a comprehensive view of which species survived the Great Dying and which did not. The findings, published in a series of 14 papers in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, contribute to a broader understanding of this pivotal period in Earth’s history.

Unraveling the Permian Era

The Permian Period, which began approximately 299 million years ago and ended with the mass extinction event known as the Great Dying, saw the extinction of around 70 percent of terrestrial species and 81 percent of marine life. This period marked the end of the Paleozoic Era, a time when life transitioned from the sea to land, leading to the flourishing of amphibians and reptiles in diverse ecosystems.

Previously, much of what was known about the transition from the Permian to the Mesozoic Era came from the Karoo Basin in South Africa. The recent findings suggest that the fossil sites in Tanzania and Zambia may provide a more comprehensive understanding of life during this critical time.

Significant Discoveries in Africa

The research team, which includes Kenneth Angielczyk, curator of paleomammalogy at the Field Museum, focused their efforts on three basins in Southern Africa: the Luangwa Basin in eastern Zambia, the Mid-Zambezi Basin in southern Zambia, and the Ruhuhu Basin in southern Tanzania. Sidor described the fossils from these regions as “absolutely beautiful” and indicative of the vibrant ecosystems that existed prior to the mass extinction.

Among the discoveries were new species of dicynodonts, small, burrowing herbivores that evolved to possess tusks and beak-like snouts. These creatures emerged during the mid-Permian and became the primary plant-eating species by the time of the Great Dying. Additionally, the team identified a new species of gorgonopsians, saber-toothed predators, and a large salamander-like amphibian, classified as a new temnospondyl species.

Sidor highlighted the significance of these findings, stating, “We can now compare two different geographic regions of Pangea and see what was going on both before and after the end-Permian mass extinction.” This research opens new avenues for understanding the survival and extinction patterns of species during this transformative period.

After completing their analyses, the team plans to return all collected fossils to Tanzania and Zambia, ensuring that these valuable resources remain accessible for future research.

This groundbreaking study not only enhances our understanding of the Permian Period but also underscores the ongoing importance of paleontological research in deciphering the complexities of Earth’s evolutionary history.