Researchers at Virginia Tech have discovered that dogs can play a crucial role in detecting the invasive spotted lanternfly, providing conservationists with a promising tool to address this growing environmental threat. The study marks the first time that canines have been shown to assist in identifying this pest, which has been wreaking havoc on agricultural sectors across the United States.

The spotted lanternfly is originally from Asia and was first identified in the United States in 2014 in Pennsylvania. Since then, it has spread to 19 states, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). The insect feeds on various plants, releasing a sugary substance known as honeydew, which fosters mold growth and damages crops. Due to its destructive nature, some states have initiated campaigns urging residents to stomp on the pests upon sight.

Dogs Prove Their Worth in the Field

In the study, pet dogs were trained to locate the egg masses of the spotted lanternfly, which pose a significant challenge for eradication efforts. Egg masses often resemble dried mud, making them difficult to spot for the untrained eye. This is where dogs can leverage their exceptional sense of smell.

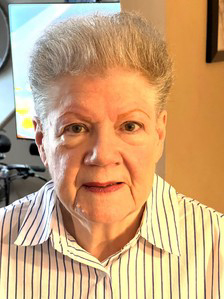

“Dogs have one dominant sense. It’s their nose. We use our eyes. Dogs use their nose like their eyes,” said Katie Thomas, a participant in the study, who trained her nine-year-old pit bull mix, Finch, to identify the target scent. Throughout the study, dogs underwent both indoor and outdoor tests, receiving rewards for successfully locating egg masses.

Thomas expressed her enthusiasm for applying her dog’s skills to a real-world problem: “To be able to do things that we already do, that we are having a lot of fun with… train our dogs to sniff stuff, being able to apply that to something like a real problem that affects our community is really fulfilling.”

Promising Results from Canine Detection

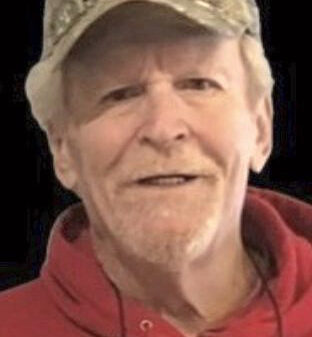

Another participant, Carolyn Shelburne, and her nine-year-old border collie, Hermes, were among the first teams to successfully complete their field tests. In total, 182 volunteer teams from across the U.S. participated in the study. The results were impressive: dogs correctly identified the lanternfly scent more than 80% of the time in controlled indoor tests and over 60% of the time in real-world outdoor scenarios, outperforming typical human searches.

“They are everywhere, and we need to search out the eggs. The problem is it’s too late once we have the lanternfly,” Shelburne noted, highlighting the urgency of the situation.

Both Thomas and Shelburne hope that this study will inspire others to train their dogs for similar purposes. “Hopefully, more people will see that you can train any dog to do this, and it gives you something fun to do with your dog,” Shelburne said.

As the fight against the spotted lanternfly continues, researchers at Virginia Tech are optimistic about the future role of dogs in environmental conservation. Beyond detecting this particular pest, there is potential for training dogs to identify other invasive species, enhancing efforts to protect local ecosystems.