Recent excavations at the East Farm site in Barnham, Suffolk, have revealed what may be the oldest evidence of deliberate fire-making by Neanderthals, dating back approximately 400,000 years. This discovery significantly predates previous findings by more than 350,000 years and suggests that these ancient humans had mastered the ability to create fire independently of early modern humans.

The research team, led by archaeologists from the British Museum, unearthed a series of compelling artifacts during ongoing excavations that began in 2013. Among the findings were reddened silt, heat-distorted flint handaxes, and fragments of iron pyrite, a mineral that can produce sparks when struck against flint. According to Dr. Chris Ashton, a leading researcher on the project, “In over 36 years of fieldwork and geological studies in the area, we’ve never found pyrite before. The only time we find it is alongside heat-shattered handaxes and baked sediments.”

Determining whether early humans intentionally ignited fires poses a complex challenge. The archaeological traces of natural fires and human-made fires are often indistinguishable. Nevertheless, the combination of evidence from East Farm strengthens the case for deliberate fire-making. The presence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, chemicals typically formed by burning wood, along with geomagnetic changes in the sediment, suggest that fires were repeatedly set at this location.

Significance of the Findings

These findings could revolutionize our understanding of Neanderthal behavior and their capacity for using fire. Dr. Ashton emphasized the significance of these discoveries, stating, “If the ability to light fires is so ancient, we can assume that the mastery of fire and its habitual use dates back even further.”

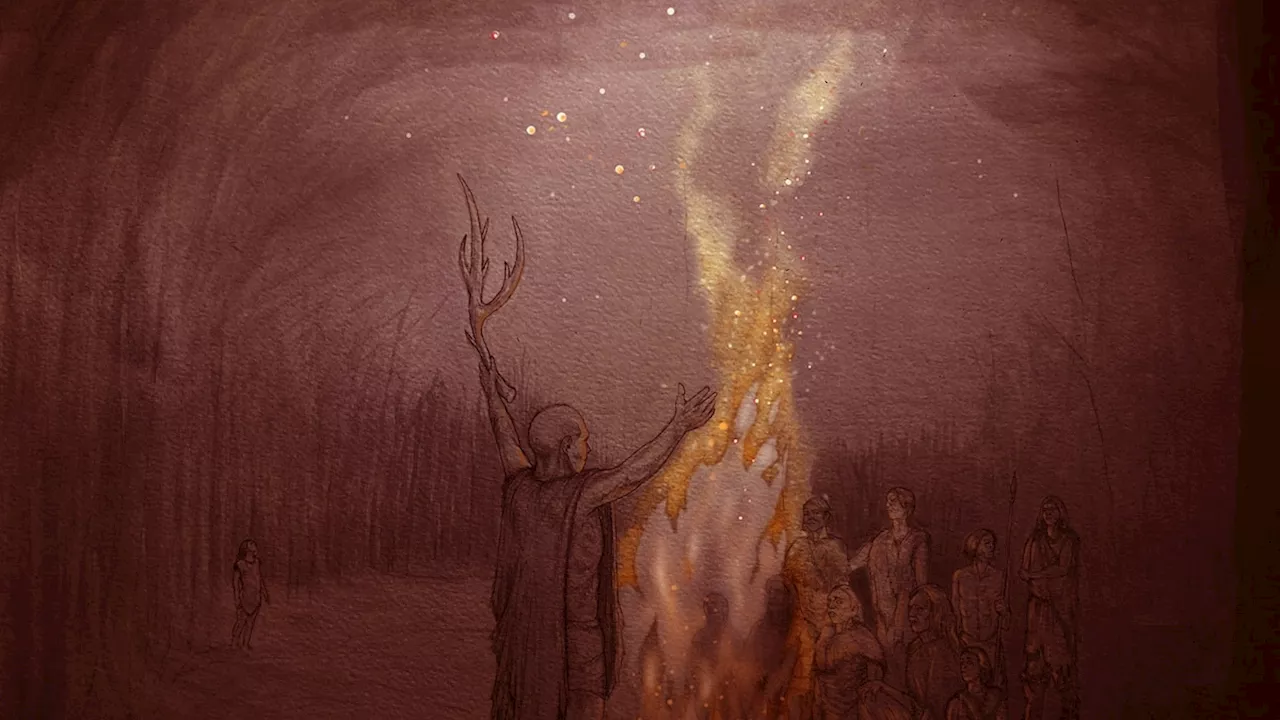

Fire has played a crucial role in human evolution, influencing biological and social developments. It provided warmth, protection from predators, and a means to cook food. Furthermore, fire features prominently in various human belief systems and allowed early humans to inhabit colder regions effectively.

The East Farm site was initially discovered over a century ago when it was used as a clay pit. Subsequent excavations revealed stone tools from the Lower Paleolithic period, suggesting that early human ancestors inhabited the area when Britain was still connected to the European continent by a land bridge. While other prehistoric sites have shown evidence of fire usage, the distinction at East Farm lies in the discovery of iron pyrite, indicating a possible fire-making kit.

Research Community Reactions

The academic community has responded with interest, though opinions vary regarding the implications of the findings. While some researchers consider this evidence a significant addition to the early fire record, others express caution about confirming deliberate fire-making.

Dr. Michael Sandgathe, an expert in ancient fire practices, remarked, “The authors did an excellent job with their analysis of the Barnham data, but they seem to be stretching the evidence.” He suggests that, even if the findings are validated, they indicate that fire-making during this period was likely rare.

As the research continues, experts hope to further explore the implications of these discoveries. The East Farm site has opened new avenues for understanding the technological capabilities of Neanderthals, highlighting their potential as skilled fire users long before the advent of modern humans.

This ongoing investigation underscores the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in archaeology, combining geology and anthropology to paint a clearer picture of humanity’s distant past. The implications of mastering fire could extend beyond survival, impacting social structures and cultural practices among early human societies. The East Farm findings provide a fascinating glimpse into the lives of our ancient relatives and their enduring legacy.