Astronomers from the University College London (UCL) and the University of Warwick have discovered that aging stars may be destroying nearby giant planets. Their findings, published on November 5, 2025, in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, provide insights into the fate of planets orbiting stars that have evolved into red giants.

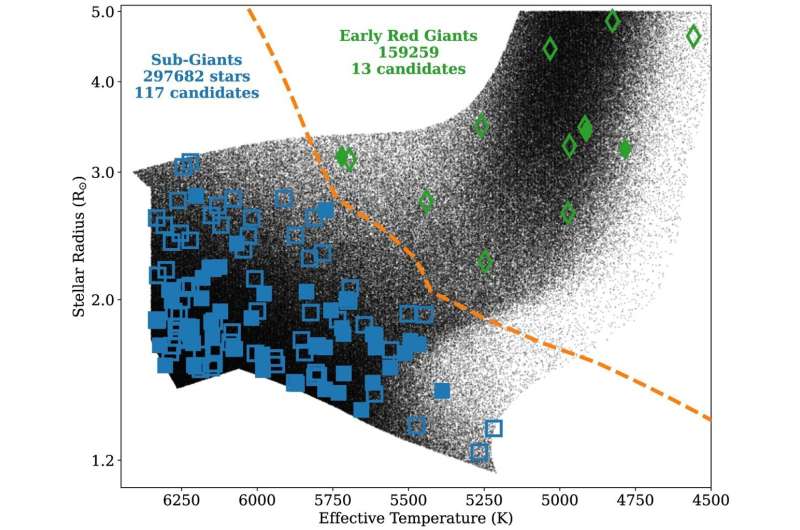

As stars like the sun exhaust their hydrogen fuel, they undergo a transformation, cooling down and expanding into what is known as the red giant phase. In the case of the sun, this event is projected to occur approximately five billion years from now. The research team examined nearly half a million stars that had recently entered this phase, identifying 130 planets and planet candidates, including 33 previously unknown entities, that orbit closely around these stars.

The study revealed a significant trend: planets are less likely to exist around stars that have expanded and cooled to the red giant stage. This suggests that many such planets may have already perished due to their stars’ evolution. Lead author Dr. Edward Bryant from UCL stated, “This is strong evidence that as stars evolve off their main sequence, they can quickly cause planets to spiral into them and be destroyed.” He expressed surprise at the efficiency with which these stars seem to engulf their close planets.

The destruction of these planets is attributed to the gravitational interactions between the star and the planet, a phenomenon known as tidal interaction. As the star expands, this gravitational pull increases, ultimately drawing the planet closer until it either disintegrates or falls into the star. Dr. Bryant compared this to the way the moon influences Earth’s oceans, stating that the planets exert similar forces on their host stars.

Co-author Dr. Vincent Van Eylen also commented on the implications of the research, reflecting on the future of our own solar system. “In a few billion years, our own sun will enlarge and become a red giant. When this happens, will the solar system planets survive? We are finding that in some cases planets do not.” He noted that while Earth may be safer than the giant planets studied, its fate during the sun’s red giant phase remains uncertain, as life on Earth would likely not survive.

To conduct their study, the researchers utilized data from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). They developed a computer algorithm capable of detecting the subtle decreases in brightness that indicate an orbiting planet is passing in front of its star. The focus was on giant planets with short orbital periods, specifically those completing their orbits in no more than 12 days.

Starting with over 15,000 potential signals, the team applied rigorous testing to eliminate false positives, ultimately narrowing the list down to 130 planets and planet candidates. Among these, 48 were already known, 49 were identified as candidates awaiting confirmation, and 33 were newly detected.

The research revealed that the occurrence rate of nearby giant planets decreases as stars evolve. The overall rate was measured at just 0.28%, with younger post-main sequence stars exhibiting a higher rate of 0.35%, akin to main sequence stars. In contrast, the most evolved stars, which had sufficiently cooled and expanded to be classified as red giants, displayed a significantly reduced rate of 0.11%.

To confirm the newly detected candidates as true planets rather than low-mass stars or brown dwarfs, astronomers must calculate their mass. This involves measuring the movements of their host stars and inferring the gravitational influence of the planets, which can be observed through the wobbling motions of the stars.

Dr. Bryant emphasized the importance of determining the masses of these planets, stating, “Once we have these planets’ masses, that will help us understand exactly what is causing these planets to spiral in and be destroyed.”

The findings not only shed light on the fate of planets in our galaxy but also raise questions about the long-term survival of celestial bodies as stars evolve. As research continues, the implications for planetary systems, including our own, remain a critical area of exploration.