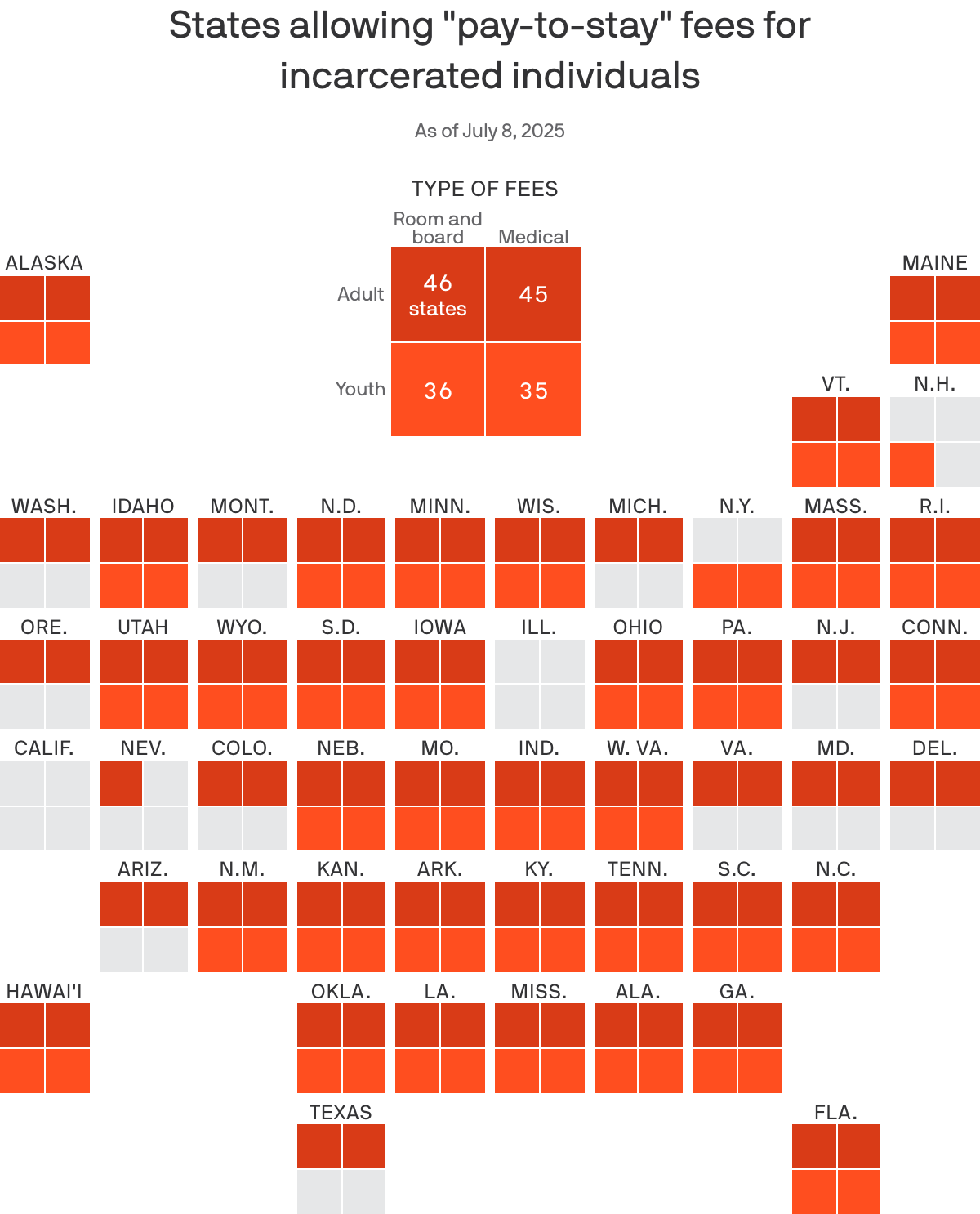

A recent review of data by Axios has revealed that nearly all U.S. states permit jails and prisons to charge incarcerated individuals for their own incarceration. This practice includes fees for medical services and “room and board,” contributing to a cycle of debt that can hinder the ability of approximately 1.8 million incarcerated people to escape poverty—often a factor in their original arrests.

The findings, compiled by the advocacy group Campaign Zero, highlight a troubling aspect of the criminal justice system. Out of 48 states in the U.S., all allow at least one category of what is known as “pay-to-stay” fees. Specifically, 42 states and the District of Columbia explicitly permit charges for room and board for adults, while 43 states allow medical fees for the same group. Additionally, 33 states and D.C. permit room and board fees for incarcerated youths, and 31 states allow medical fees for young offenders.

Only California and Illinois have eliminated all categories of these fees in their state correctional facilities. New Hampshire has repealed most fees but still allows for youth room and board charges. The reliance on these fees has raised significant questions regarding the ethical implications of charging individuals who are already facing significant financial challenges.

The process by which these fees are implemented often exacerbates the debt faced by incarcerated individuals. According to DeRay Mckesson, executive director of Campaign Zero, fees are deducted automatically from prison wages or accounts. Many incarcerated individuals earn as little as $0.50 per hour, making it nearly impossible to pay these fees while still in prison. As a result, debts accrue, creating a financial burden that continues after release.

The implications of these fees extend beyond individual hardship. Antonio “Moe” Maestas, a Democratic state senator from New Mexico and advocate for criminal justice reform, described the practice as “taxing criminal defendants.” He argues that these fees serve as a revenue source for governments without facing political backlash, even though they do not contribute to public safety. Maestas expressed surprise at the existence of these fees in New Mexico and indicated his intention to work on legislation to eliminate them.

While some fees are intended for victim restitution or funding various programs, critics point out that many individuals charged with “victimless” crimes, such as drug possession, can also face these costs. Dylan Hayre, an advocate with the Fines and Fees Justice Center, characterized these charges as “financial exploitation disguised as justice.” He emphasized the destabilizing impact that such debts can have on individuals and their communities, stating, “You’ve taken people at their most vulnerable and handed them a bill they can’t pay.”

As inflation rises and more minor offenses become felonies, the financial strain on incarcerated individuals is expected to increase. Campaign Zero is actively working to eliminate these fees across all states and plans to engage with lawmakers to present their findings and advocate for reform in the near future. The continuation of such practices raises critical questions about the intersection of poverty, justice, and government revenue in the criminal justice system.