The notion of walking 10,000 steps daily as a fitness goal has become a widely accepted standard. This target is frequently highlighted in fitness applications, smartwatches, and various health challenges, prompting many to engage in activities such as evening strolls and lunchtime walks. Despite its popularity among health professionals and patients, the origins of this figure are less rooted in scientific research than one might assume.

In the 1960s, a Japanese company launched the Manpo-kei, a pedometer whose name translates to “10,000 step meter.” Introduced around the time of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, this device established a numerical target that resonated with the public, helping to spur sales. According to David Raichlen, a professor of biological sciences and anthropology at the University of Southern California, the marketing behind the 10,000-step goal was “kind of brilliant,” even if it was arbitrary.

Over the years, researchers have explored how daily step counts correlate with health benefits. Some studies indicate that advantages like a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease can be observed starting at around 2,500 to 3,000 steps, while others suggest that health benefits plateau around 7,500 steps. Despite this, many public health campaigns continue to endorse the five-digit target, and devices such as Fitbits frequently set it as the default daily goal.

Dr. Gregg C. Fonarow, interim chief of cardiology at UCLA, supports the step count as an accessible way to convey physical activity recommendations. He maintains that walking 10,000 steps translates to approximately five miles and around 150 minutes of moderate to intense activity, aligning with established guidelines for weekly exercise. Yet, he acknowledges variability in research findings, noting that some studies indicate a plateau in risk reduction for older women around 7,500 steps, while other research suggests benefits extend beyond 10,000 steps.

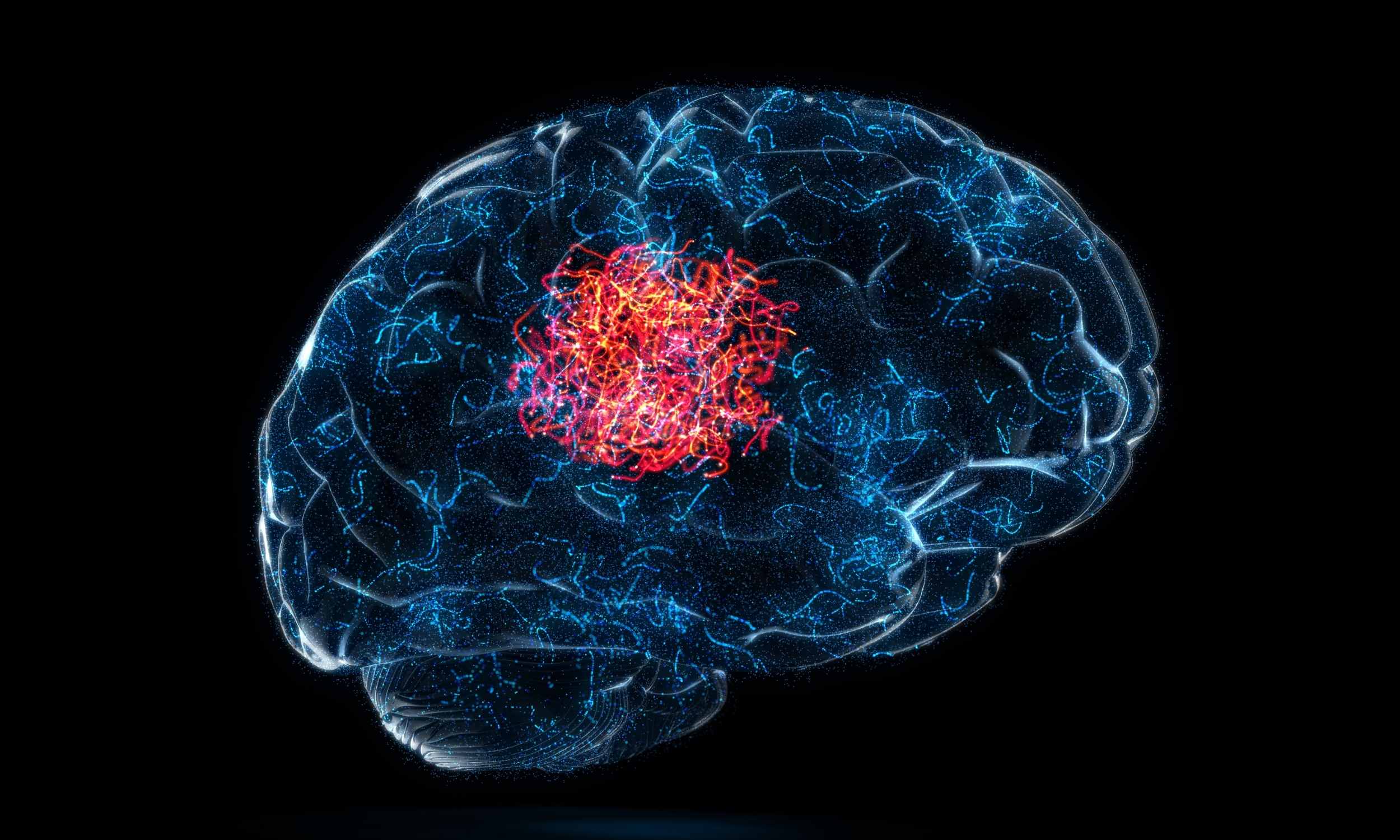

Walking is widely recognized as an effective form of exercise. Fonarow emphasizes its myriad benefits, including improved blood pressure, enhanced brain health, reduced insulin resistance, and strengthened blood vessels. Nonetheless, Raichlen advises against rigidly adhering to step counts. He believes that while 10,000 steps may serve as a motivational goal, it is not essential for maintaining good health.

“A little bit is better than nothing, and then a little bit more is better than that,” he states. The nature of walking also plays a crucial role in its health benefits. Researchers have discovered that pace—how many steps one takes per minute—affects the efficacy of physical activity. A brisk walk offers greater cardiovascular advantages compared to a slower pace, even with the same total step count.

The question remains whether there is an upper limit to these health benefits. Walking more is generally associated with a lower risk of chronic conditions, including diabetes and heart disease, but the risk reduction may plateau after a certain point. Raichlen cautions that the effectiveness of a specific step count can vary depending on factors such as age, and he highlights that discrepancies in step tracking devices can lead to different totals for the same individual.

“You can use multiple methods and end up with multiple different step counts from the exact same person,” he explains. Raichlen cites an example of his family tracking their steps at Disneyland, where differing devices yielded vastly different results. This variation illustrates the importance of using step counts as a guideline rather than an inflexible rule.

“The best thing people can do is to be their own study,” he advises, encouraging individuals to assess their current activity levels and aim to increase them gradually. Fonarow also advocates for personalized recommendations, noting that individuals who lead sedentary lifestyles may find it impractical to jump to 10,000 steps immediately.

Dr. Parveen Garg of Keck Medicine at USC echoes this sentiment, emphasizing the importance of integrating activity into daily life. While spreading activity across the week is ideal, he acknowledges that some days may naturally be more active than others. For those with limited time or energy, increasing steps on weekends or during longer breaks offers substantial health benefits.

Multiple studies indicate that the risk of cardiovascular disease and premature death diminishes notably at around 2,500 steps per day. Garg reinforces that the benefits of movement do not hinge solely on reaching 10,000 steps; they can begin much earlier.

“As humans, we like goals,” he remarks. “It does give people a goal to accomplish. In that aspect, it’s really great—as long as it does not discourage people.” He encourages his patients to focus on aerobic activity, which elevates heart rates, even if it is performed in short intervals or integrated into daily routines.

Ultimately, health experts agree that whether one walks 2,000 steps or 10,000 steps, the critical factor is consistency. Gradually increasing activity levels over time can yield significant health benefits. “Just keep moving,” Raichlen concludes, highlighting a universal principle for maintaining good health.