Yawning, often dismissed as a sign of fatigue or boredom, has been revealed to serve a crucial role in the regulation of fluid within the brain. Research conducted by a team at Neuroscience Research Australia and published in March 2024 has shown that yawning reorganizes the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), a vital liquid that cushions and nourishes the brain. This study involved advanced MRI scans of 22 healthy adults as they engaged in different breathing techniques, including yawning.

The findings challenge previous assumptions about yawning, which include theories that it primarily increases oxygen intake or helps regulate body temperature. According to Adam Martinac, a researcher at Neuroscience Research Australia, “Crocodiles yawn and dinosaurs probably yawned. It’s this incredibly evolutionarily conserved behaviour, but why is it still with us?”

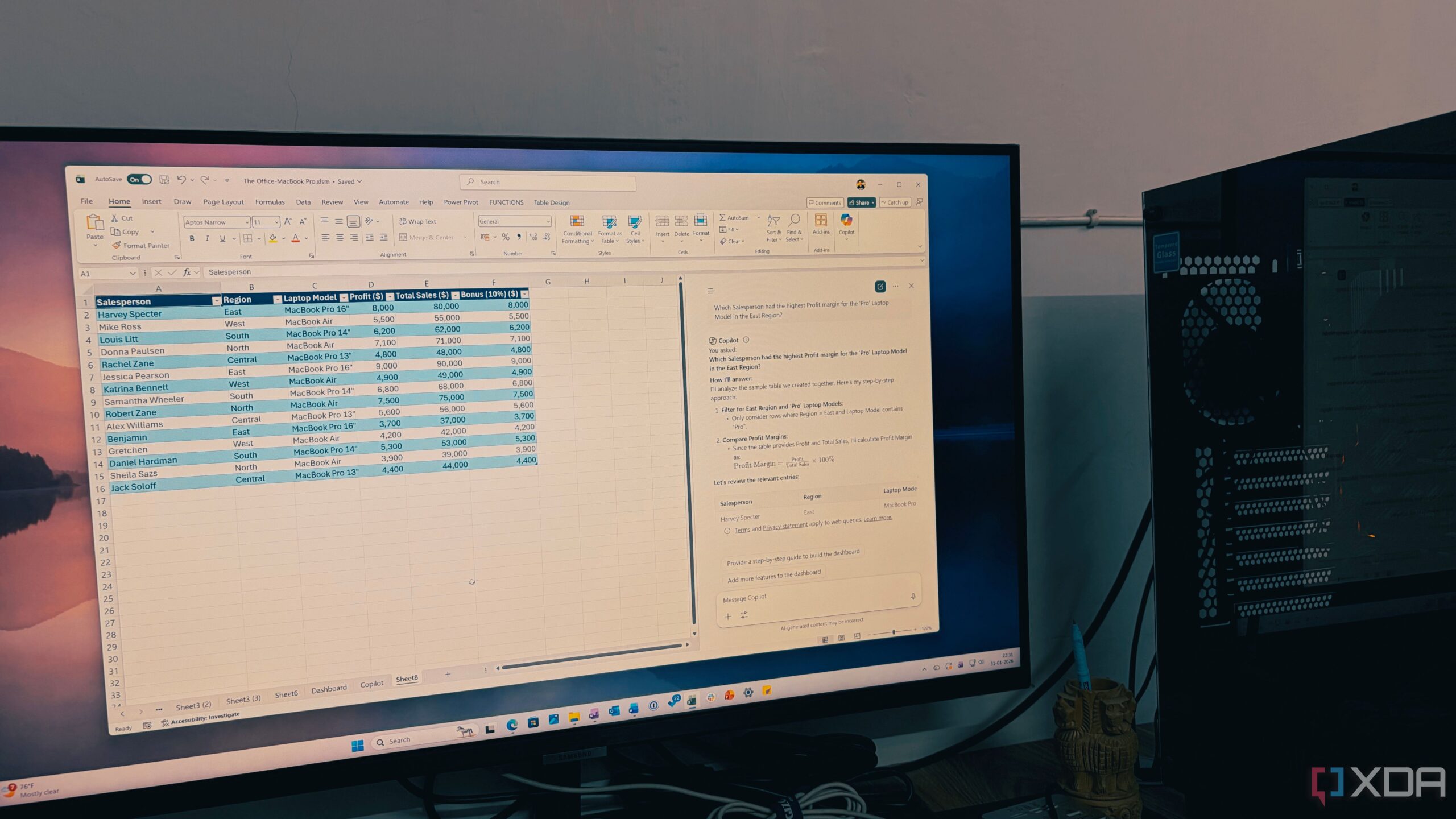

Through the study, participants performed yawning alongside normal breathing, suppression of a yawn, and forceful deep breathing. Initial hypotheses suggested that yawning would produce similar effects to deep breathing regarding CSF movement. Instead, the data revealed an unexpected result: yawning prompted the movement of CSF out of the brain, while deep breathing did not.

The research team discovered that during a yawn, CSF and venous blood flow were strongly coupled, moving together away from the brain toward the spinal column. In contrast, during deep breaths, these fluids typically flowed in opposing directions. Martinac noted, “We’re just sitting there like, whoa, we definitely didn’t expect that.”

The fluid dynamics observed during yawning also resulted in an increase of over 34% in carotid arterial inflow compared to deep breathing. This significant change occurs because yawning allows for the simultaneous outflow of both CSF and venous blood, thereby creating space for additional arterial inflow.

Another notable aspect of the study was the uniqueness of each participant’s yawn. Each volunteer exhibited a distinct yawning pattern, suggesting that individuals possess what Martinac describes as a “yawning signature.” Future research aims to investigate the implications of these findings, particularly the benefits of CSF movement during yawning.

The team is also exploring the potential reasons behind yawning’s contagious nature. During the MRI sessions, participants were encouraged to yawn by watching videos of others yawning, which highlights the social aspects of this behavior. Martinac humorously mentioned, “Whenever we have my lab meetings or I do a presentation, I always have to go last because if I start talking about my research, everyone starts yawning.”

The study has garnered attention from other experts in the field. Andrew Gallup from Johns Hopkins University acknowledged the valuable contributions of this research, particularly regarding its implications for thermoregulation. He noted that the increase in internal carotid arterial flow during yawning is a significant finding that deserves more emphasis in the study’s presentation.

Conversely, Yossi Rathner from the University of Melbourne offered a different interpretation, suggesting that yawning might help clear adenosine, a chemical linked to sleep-wake regulation, from the brain. This action could alleviate sleep pressure and enhance alertness.

As this research unfolds, it opens up new avenues for understanding the physiological functions of yawning and its potential benefits. The intricate relationship between yawning and fluid dynamics in the brain highlights the complexity of this seemingly simple behavior and its evolutionary significance.