Research from a study conducted by Izak Yasrebi-de Kom, PhD, at the Amsterdam University Medical Center, reveals that the antibiotic vancomycin poses a greater risk of acute kidney injury (AKI) compared to alternatives such as clindamycin and linezolid. This finding emphasizes the importance of adhering to existing prevention strategies for AKI in intensive care unit (ICU) settings.

The study examined the consequences of initiating vancomycin versus alternative antibiotics on the 14-day risk of AKI for adult patients admitted to ICUs. The results indicated a significantly higher risk associated with vancomycin, prompting the authors to recommend various strategies. These include dosing adjustments based on renal function, ongoing therapeutic drug monitoring, and considering non-nephrotoxic alternatives when appropriate.

“AKI is a frequent syndrome in ICU patients and is often caused by drugs,” stated Yasrebi-de Kom and his research team. They believe that optimizing medication regimens could mitigate the risk of drug-induced AKI and its related negative outcomes.

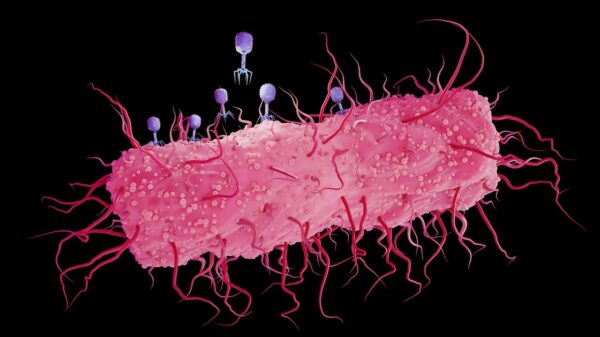

Vancomycin, a tricyclic glycopeptide antibiotic used primarily for severe gram-positive bacterial infections, has been linked to several adverse reactions, including nephrotoxicity. Despite its common use, the evidence regarding its role in causing AKI among adult ICU patients has been inconsistent.

To investigate this issue, the researchers employed a target trial emulation study, utilizing data from electronic health records (EHRs) of patients across 15 Dutch ICUs from January 2010 to December 2019. They linked this data with the Dutch National Intensive Care Evaluation quality registry, focusing on adult, non-dialysis dependent patients who were AKI-free upon admission and suspected of having bacterial infections treatable with either vancomycin or one of six alternative antibiotics: clindamycin, linezolid, teicoplanin, meropenem, cefazolin, or daptomycin.

Eligible patients were those who had undergone admission for at least 24 hours but less than seven days. A baseline serum creatinine measurement within the first 24 hours of ICU admission was also a prerequisite for inclusion.

The follow-up for the hypothetical trial began at the time of treatment assignment and concluded upon diagnosis of AKI, loss to follow-up, initiation of an alternative treatment strategy, or 14 days after treatment assignment.

Among a total of 176,489 ICU admissions, 30,510 patients initiated one of the treatment strategies, with 1,809 meeting all eligibility criteria. Of these, 887 patients initiated vancomycin, while 922 began treatment with an alternative antibiotic.

After adjusting for variables, the study found that initiating vancomycin was associated with a heightened risk of AKI at 14 days compared to starting an alternative antibiotic (0.28; 95% CI, 0.21 to 0.34 versus 0.17; 95% CI, 0.14 to 0.20; risk difference, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.04 to 0.19). Notably, no significant difference was observed at the two-day mark.

In a deeper analysis focusing on dose-response relationships, the researchers found that both higher and lower doses of vancomycin correlated with increased AKI risk at 14 days when compared to alternative antibiotics. The higher dose showed a more pronounced risk difference (0.17; 95% CI, 0.05 to 0.25 versus 0.10; 95% CI, 0.01 to 0.19).

“Our findings indicate that vancomycin causes a higher risk of AKI compared to the investigated alternative antibiotics,” concluded the researchers. “We recommend clinicians to comply with clinical vancomycin-induced AKI prevention strategies. Future research on dose-response relationships is warranted.”

This study underscores the need for heightened awareness and careful management of antibiotic use in critical care settings to minimize the risk of kidney injury among vulnerable patients.