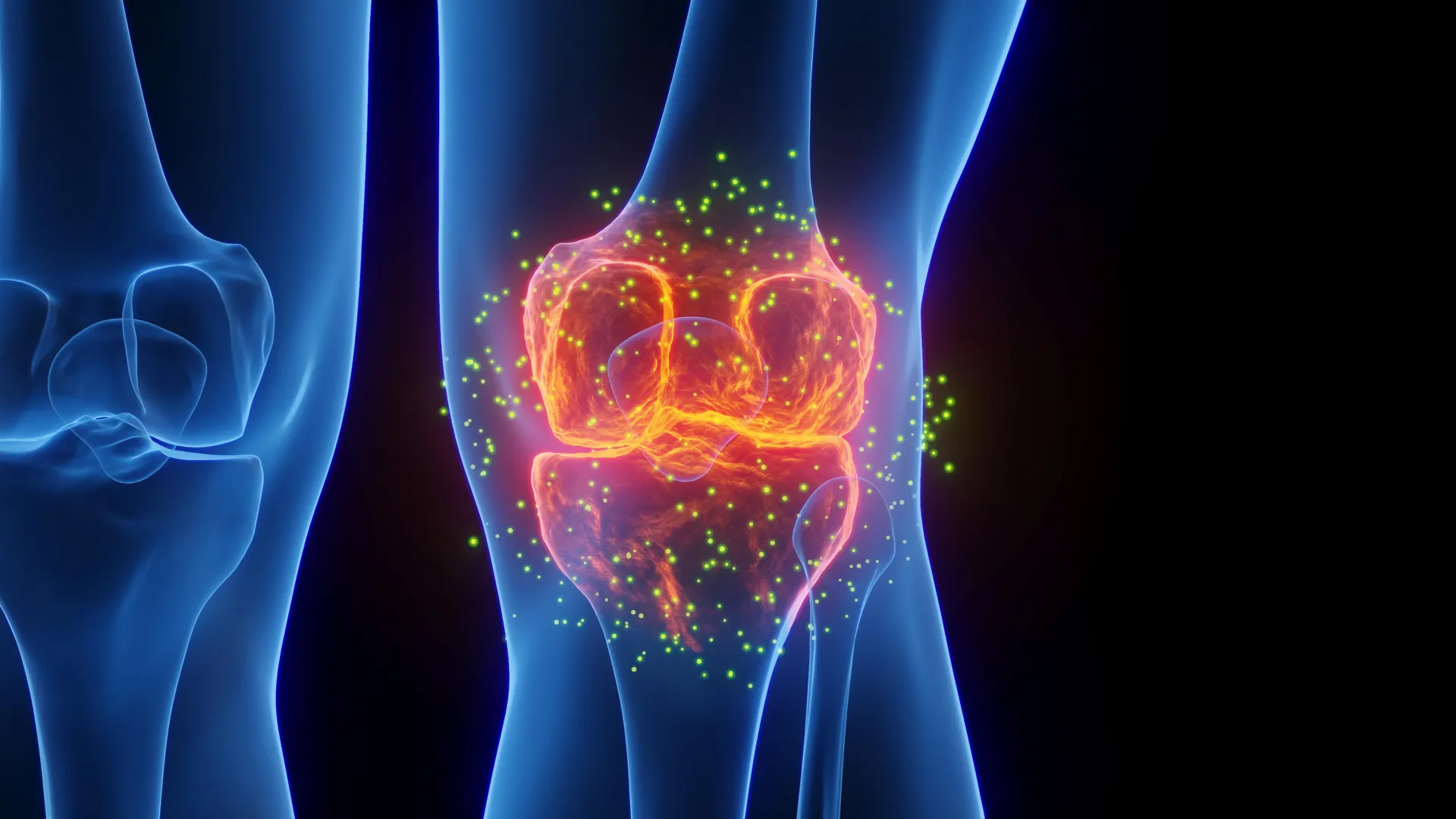

Researchers at Stanford Medicine have developed a groundbreaking treatment capable of regenerating cartilage and potentially preventing arthritis, particularly after knee injuries. This innovative therapy, unveiled on January 20, 2026, works by blocking a protein associated with aging, resulting in the restoration of healthy cartilage in older mice and damaged joints.

The findings indicate promising implications for both aging populations and athletes who often suffer from injuries. The treatment not only reversed cartilage loss in aged mice but also inhibited the onset of arthritis following knee injuries that mimic anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears, common in various sports.

Significant Advances in Joint Health

The research team, led by Helen Blau, PhD, and Nidhi Bhutani, PhD, focused on a protein known as 15-PGDH, which tends to increase in levels as organisms age. This protein has been identified as a driving factor behind tissue degradation. By inhibiting 15-PGDH with a targeted injection, the scientists observed a remarkable improvement in joint function and mobility, as the treatment encouraged the regeneration of shock-absorbing cartilage.

In addition to animal studies, human cartilage samples collected from knee replacement surgeries responded positively to the treatment. The tissue displayed early signs of regeneration, suggesting that similar therapies could one day be used to restore cartilage in humans, decreasing the need for joint replacement surgeries.

Shifting the Paradigm in Osteoarthritis Treatment

Osteoarthritis affects approximately one in five adults in the United States, contributing to an estimated $65 billion in direct healthcare costs annually. Current treatment options primarily focus on pain management or surgical interventions. This new approach, however, targets the underlying causes of cartilage damage, which could represent a pivotal shift in how osteoarthritis is treated.

The study highlights the role of 15-PGDH in the age-related decline of cartilage. In previous research, higher levels of this protein were linked to reduced muscle strength, and its inhibition has been shown to enhance muscle mass in older mice. The current study extends this understanding to cartilage regeneration, revealing that the therapy can induce chondrocytes—cartilage-producing cells—to revert to a more youthful state without the involvement of stem cells.

“This is a new way of regenerating adult tissue, and it has significant clinical promise for treating arthritis due to aging or injury,” said Blau. The study, published in the journal Science, underscores the potential for developing effective treatments that can restore joint health and significantly improve the quality of life for millions suffering from joint pain.

With initial clinical trials underway for an oral version of the treatment, researchers are optimistic about its future application in human patients. If successful, this breakthrough could revolutionize the management of osteoarthritis, potentially allowing for regeneration of existing cartilage and eliminating the need for invasive procedures.

The research received support from the National Institutes of Health and various foundations dedicated to advancements in medical science, including the Baxter Foundation for Stem Cell Biology and the Li Ka Shing Foundation. As the science progresses, the potential to harness this therapy for broader applications in joint health remains an exciting prospect for both researchers and patients alike.