A recent study conducted by researchers at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology in collaboration with colleagues at Columbia University has uncovered significant differences in the immune systems of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Published on September 30, 2025, in the journal Nature, the findings point to the immune system’s potential involvement in the disease’s progression and suggest new avenues for treatment.

The research highlights how the immune response in ALS patients skews the balance between inflammatory and anti-inflammatory chemicals in the brain. This imbalance could provide insights into why some individuals with ALS experience longer survival times than others. By 2030, it is estimated that 32,000 Americans will be affected by this devastating condition.

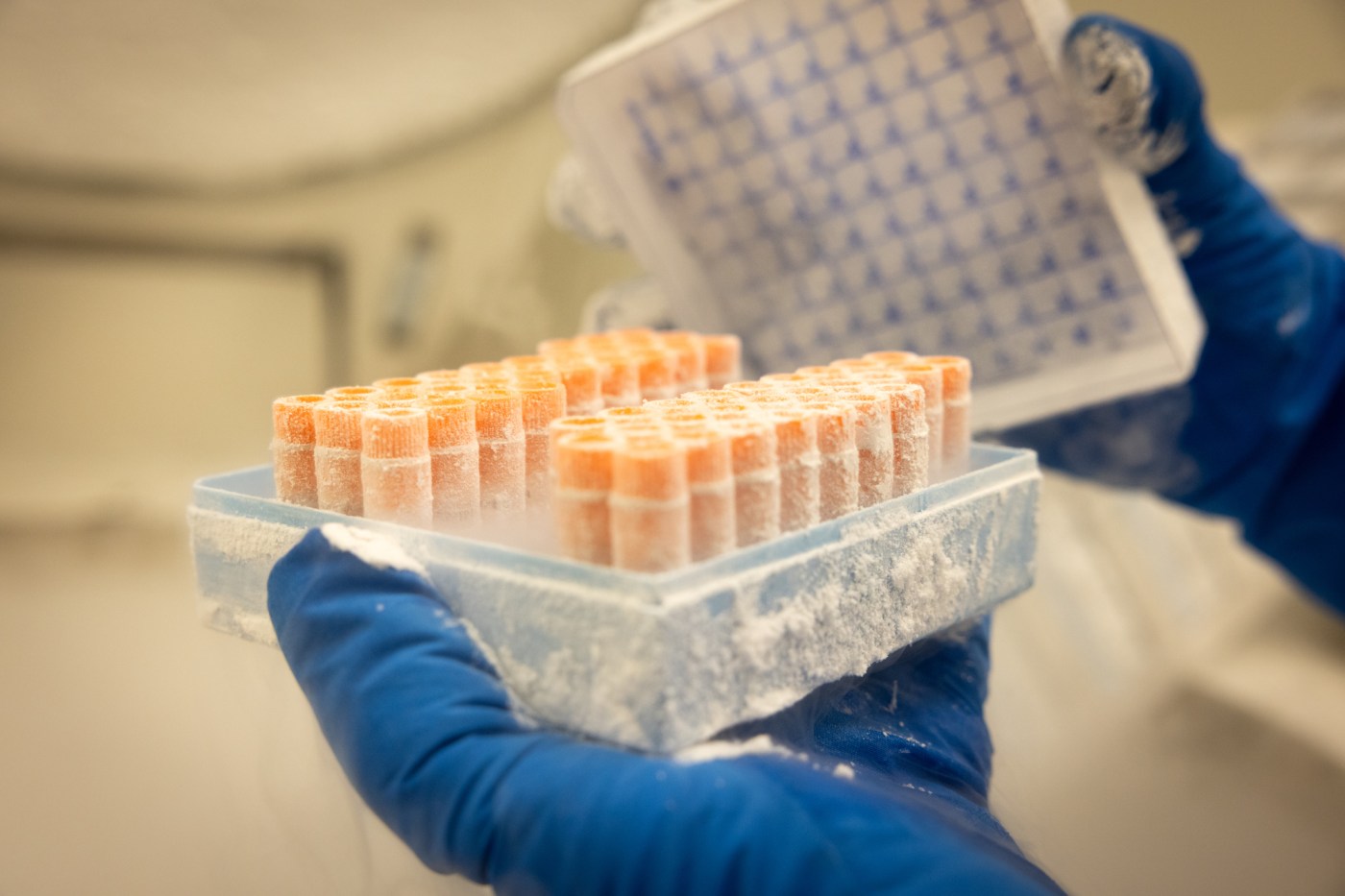

Researchers discovered that T cells—vital components of the immune system—exhibit altered behavior in blood samples from ALS patients compared to those from healthy donors. While individuals with mutations affecting the C9orf72 protein exhibited more pronounced differences, the overall trend was evident across all ALS patients, regardless of genetic mutations.

Alessandro Sette, an immunologist at the La Jolla Institute and co-lead of the study, remarked on the implications of these findings. He noted that the immune response in ALS resembles the mechanisms seen in other autoimmune diseases, such as diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis, where the immune system attacks healthy tissue. “This is the first identification of the protein as being associated with ALS in terms of the immune activity,” Sette stated. He emphasized the connection between anti-inflammatory responses and improved outcomes in patients.

Statistics from the ALS Association indicate that the average survival time post-diagnosis is approximately three years. However, survival rates show significant variability: 20% of patients live for five years, 10% reach ten years, and a mere 5% survive for 20 years or more. Historical cases, such as that of renowned physicist Stephen Hawking, who lived with the condition for 55 years, further illustrate this disparity.

The research suggests that patients who live longer with ALS often have immune systems that produce higher levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines. According to Sette, this finding raises the possibility of developing therapies aimed at enhancing the anti-inflammatory response to protect brain health. “One potential way to intervene is to basically try to lean on the immune system to generate more of the anti-inflammatory rather than the inflammatory reaction,” he explained.

Dr. Stanley Appel, a neurologist at Houston Methodist Hospital, acknowledged the significance of the study’s conclusions. He expressed that the observations documented in the research could lead to potential therapeutic targets for ALS. “It is eminently clear that immune activation promotes inflammation and, in turn, neuron cell injury and loss,” Appel noted. He emphasized the importance of understanding the complex interactions among various immune cells to mitigate the damage caused by inflammation.

As research continues to unravel the complexities of ALS, the insights gained from this study offer hope for new treatment strategies that could improve the quality of life for those affected by the disease. The connection between the immune system and ALS underscores the need for further investigation into potential interventions that could alter the course of this debilitating condition.