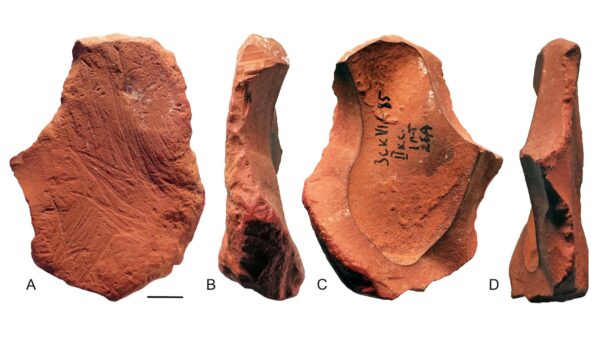

In a groundbreaking study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, archaeologists have uncovered the remains of an infant dating back to the Copper Age, approximately 4,000 to 5,000 years ago, in a well near Faenza, Italy. The discovery, made by a team from the University of Bologna, offers new insights into the health, ancestry, and life of prehistoric populations in Europe. Despite the skeletal remains being severely degraded, advanced scientific techniques, including dental histology, radiocarbon dating, and ancient DNA analysis, enabled researchers to reconstruct crucial aspects of the infant’s early life.

The Significance of Advanced Scientific Techniques

The excavation, which took place prior to a planned construction project, initially revealed very little about the remains due to their poor condition. However, the researchers were undeterred, employing an interdisciplinary approach that included not only traditional osteological analysis but also cutting-edge techniques like paleoproteomics and biogeochemistry. These methods allowed the team to glean new details from the fragmented bones and teeth, opening a window into the distant past that would otherwise remain closed.

Lead author Owen Alexander Higgins, a research fellow at the University of Bologna, underscored the importance of these findings. He explained,

“Our research shows that even highly degraded osteological materials hold important information if examined using advanced methods.”

By examining the infant’s teeth, including a baby molar and a developing permanent molar, scientists were able to estimate the child’s age at death—around 17 months. This discovery provided a window into the infant’s early years and overall health, revealing that the child had not experienced signs of malnutrition or developmental stress, suggesting a relatively healthy start to life.

Revealing the Child’s Sex and Genetic Origins

Determining the sex of the infant was challenging due to the fragmented nature of the remains, but further analysis confirmed the child was male. This was established through proteomic analysis of the dental enamel and a detailed examination of the bone fragments. However, it was the discovery of a rare mitochondrial haplogroup, V+@72, that has drawn significant attention from researchers.

This genetic marker has previously been discovered in only one other ancient sample from the Eneolithic necropolis of Serra Cabriles in Sardinia. The presence of this rare haplogroup is significant because it has primarily been associated with the Saami people of northern Europe and populations along the Cantabrian coast in Spain.

The presence of such a rare haplogroup challenges our perceptions of the geographic reach and movement of populations in the Copper Age, offering a glimpse into a more interconnected ancient Europe.

Implications for Understanding Prehistoric Europe

What makes this discovery particularly intriguing is that the haplogroup is very rare in modern European populations, suggesting that there were long-distance connections between the populations of southern Italy and those in the far north of the continent, particularly in areas far beyond the Alps. This raises questions about prehistoric migration patterns and cultural exchanges that were previously not well understood.

Experts believe that these findings could reshape our understanding of prehistoric Europe. Dr. Maria Rossi, an anthropologist specializing in ancient European cultures, notes that

“This discovery could indicate that prehistoric communities were far more interconnected than previously thought, possibly through trade routes or shared cultural practices.”

Such insights could lead to a reevaluation of how prehistoric societies interacted with one another across vast distances.

Future Research and Exploration

The discovery of the infant’s remains and the subsequent analysis have opened new avenues for research into prehistoric human migration and interaction. Future studies may focus on uncovering more about the social structures, trade practices, and environmental adaptations of these ancient populations. Researchers are hopeful that similar discoveries could be made in other parts of Europe, providing a broader understanding of the continent’s ancient history.

As archaeologists continue to employ advanced scientific techniques, the potential for uncovering hidden aspects of our past remains vast. The findings from Faenza not only contribute to our knowledge of ancient populations but also highlight the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in archaeology, offering a more comprehensive view of human history.