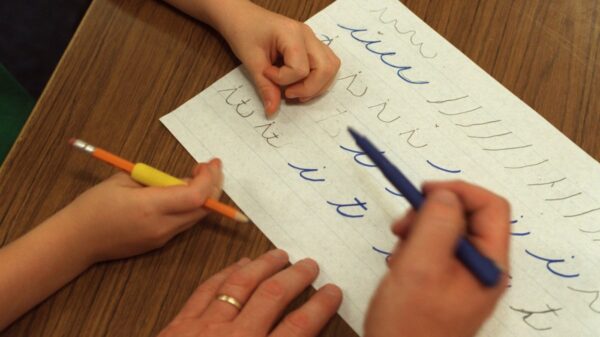

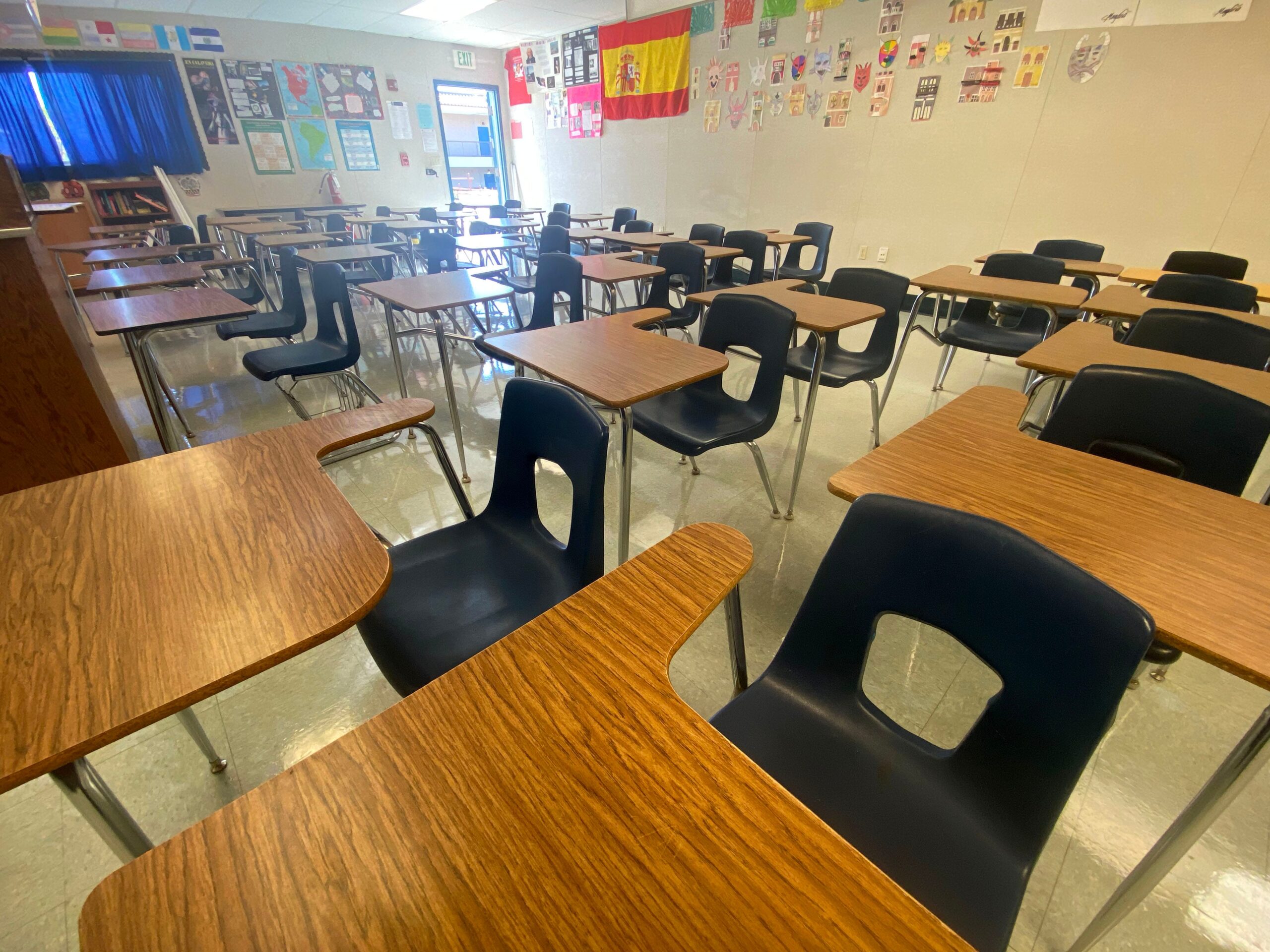

California, often perceived as a progressive leader, is now confronted with a troubling reality regarding public school segregation. A recent study by the Civil Rights Project at UCLA reveals that the state’s public schools are experiencing some of the highest levels of racial and socioeconomic segregation in the United States. Over the past three decades, the proportion of intensely segregated schools—those with more than 90% students of color—has surged to 44.5%, affecting nearly half of California’s public K-12 institutions.

This alarming trend contradicts California’s national reputation as a proponent of equitable policies. According to Ryan Pfleger, a senior policy research analyst and co-author of the report, the findings underscore a longstanding issue. “There has definitely been a trend toward increasing segregation, both nationally and in California, for 30 or so years,” he stated. Notably, California now has the highest proportion of intensely segregated schools among all states in the continental U.S.

The disparities are stark. Schools predominantly attended by White and Asian students benefit from better funding, more resources, and higher graduation rates compared to those with significant populations of Black, Latino, Native American, and multiracial students. Pfleger emphasized the importance of addressing these inequalities: “When we have schools that are radically unequal in those regards, then we have a set of students with access to opportunities and a set that does not have that access.”

Research has consistently shown that diverse school environments promote positive academic and social outcomes for all students. Conversely, schools that are deeply segregated contribute to unequal learning experiences, leading to poorer health outcomes, higher poverty rates, and diminished long-term economic prospects for students in those settings. In essence, students attending schools with predominantly non-White populations tend to struggle more both during their K-12 education and beyond.

The root causes of this segregation mirror broader demographic shifts in California. Since the 1990s, the state has seen a dramatic increase in its Latino population, which is reflected in school enrollment figures. Research from the Civil Rights Project indicates that between 1990 and 2022, White enrollment in public K-12 schools decreased by 1 million, while Latino enrollment grew by 1.4 million. During this period, California’s overall population increased by approximately 10 million.

Yet, demographic changes alone do not fully explain the variations in segregation across different districts. For instance, the San Bernardino City Unified School District transitioned from having no intensely segregated schools to over 70, representing more than 90% of its total schools. In contrast, the Santa Ana Unified School District has all of its schools classified as intensely segregated since 2018.

California effectively abandoned formal desegregation efforts in the 1980s, particularly after the passage of Proposition 1 in 1979, which prohibited the use of busing for integration. A decade later, a federal judge dismissed the final defendant in a case aimed at desegregating Los Angeles’ public schools, marking a significant setback for integration efforts.

Since then, both magnet and charter schools have witnessed a marked shift toward racial isolation. Initially intended to foster integration through specialized programs, many magnet schools have become more selective, emphasizing standardized test scores as admission criteria. For example, within the Los Angeles Unified School District, there are 56 magnet programs catering to “gifted” or “highly gifted” students, often imposing restrictive academic requirements.

The consequences of this educational segregation are profound. The report found that graduation rates in schools with a high proportion of White and Asian students were nearly 10 percentage points higher than in those with predominantly Black and Latino students. A significant gap also exists regarding completion of the “A-G” requirements necessary for admission to the University of California and California State University systems.

Addressing California’s growing educational divide requires a multifaceted approach. Possible solutions include reinstating public transportation to facilitate integration by allowing students from underfunded schools to attend more diverse schools in different districts. Additionally, policymakers could consider linking state funding for charter and magnet schools to their levels of integration, which may incentivize desegregation efforts.

Furthermore, enhancing affordable housing and enforcing fair housing laws could help maintain communities of color in areas where they have historically resided. Despite the lack of political momentum behind these ideas, Pfleger remains hopeful: “There is actually a lot of opportunity to change this.”

The challenge of school segregation in California remains unresolved, revealing significant disparities that threaten the educational landscape. As the state grapples with these issues, it must confront the growing divide that persists three decades on, recognizing that ignoring the problem will not make it vanish.