California regulators are poised to make a significant decision regarding water extraction limits from the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. This decision, tied to the Bay-Delta Plan, has the potential to reshape water supplies for urban areas, agricultural operations, and delicate ecosystems across the state. The plan, which is nearing final approval, mandates increased freshwater flows in rivers and estuaries, directly limiting the volume of water that can be pumped south for much of the year.

Recent public hearings highlighted the high stakes involved in the Bay-Delta Plan. Conservation groups assert that the ecological decline of the Delta necessitates urgent reform. Conversely, agricultural districts and urban water agencies caution that the proposed changes could disrupt supply chains, severely impact the agricultural sector, and lead to higher water costs for households.

The Delta has historically functioned as a vital pumping hub for Central Valley agriculture, which includes almond orchards, dairy farms, and tomato processing facilities. These industries depend on water exported via the State Water Project (SWP) and the Central Valley Project (CVP). The new flow requirements under the Bay-Delta Plan could significantly limit water availability for these exports, particularly during years of below-average rainfall.

Agricultural coalitions have voiced criticism of the plan, claiming it prioritizes fish populations over food production. They argue that this “overcorrection” fails to consider the economic ramifications for farmers. In response, conservation advocates contend that decades of over-extraction have pushed crucial species, such as salmon and steelhead, to the brink of extinction.

Understanding the Bay-Delta Plan requires a look at California’s extensive water infrastructure. The Central Valley Project, initiated during the Great Depression, was designed to stabilize agricultural production and manage floods by moving water from northern California to the San Joaquin Valley. Operated by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the CVP is now a complex network of reservoirs, canals, and pumping stations providing irrigation to some of the most productive agricultural regions in the United States.

Similarly, the State Water Project, approved by voters in 1960, was established primarily to supply urban areas, delivering water from the Bay Area to Southern California and serving agricultural needs in the San Joaquin Valley. The project includes major infrastructure such as the Oroville Dam and the California Aqueduct.

Urban water users may face immediate financial impacts if the Bay-Delta Plan is enacted. According to the California Chamber of Commerce, if metropolitan water agencies receive reduced supplies from the Delta, they will likely need to raise rates to cover the costs associated with sourcing alternative water supplies. Under Proposition 218, these increases must be justified by demonstrated expenses, leading to moderate but noticeable rate hikes for many households.

The Delta is critical for maintaining the balance between freshwater rivers and the Pacific Ocean. Excessive pumping can lead to saltwater intrusion, which contaminates drinking and irrigation water. State regulators assert that the proposed flow requirements are essential for preserving the Delta’s natural defenses against salinity intrusion. Yet, local water districts have raised concerns that fixed flow standards may lack the necessary flexibility during extreme drought conditions.

The plight of the Delta smelt, a once-abundant fish species now nearing extinction, has become emblematic of the ongoing water management conflict in the Bay-Delta region. Advocates for conservation view the smelt as a key indicator of the Delta’s ecological health, while critics argue that regulatory measures surrounding the species have gone too far. Regardless of its future, the smelt’s legal protection continues to influence the amount of freshwater that must remain in the Delta each year.

As California regulators prepare to vote on the Bay-Delta Plan in March 2024, the potential for conflict looms large. The plan may become a contentious issue, especially with the Trump administration’s past support for increasing water deliveries to agricultural districts. State officials maintain that California has both the authority and the obligation to safeguard the Delta, while water users express concern that conflicting regulations could create uncertainty as agencies strategize for long-term investments.

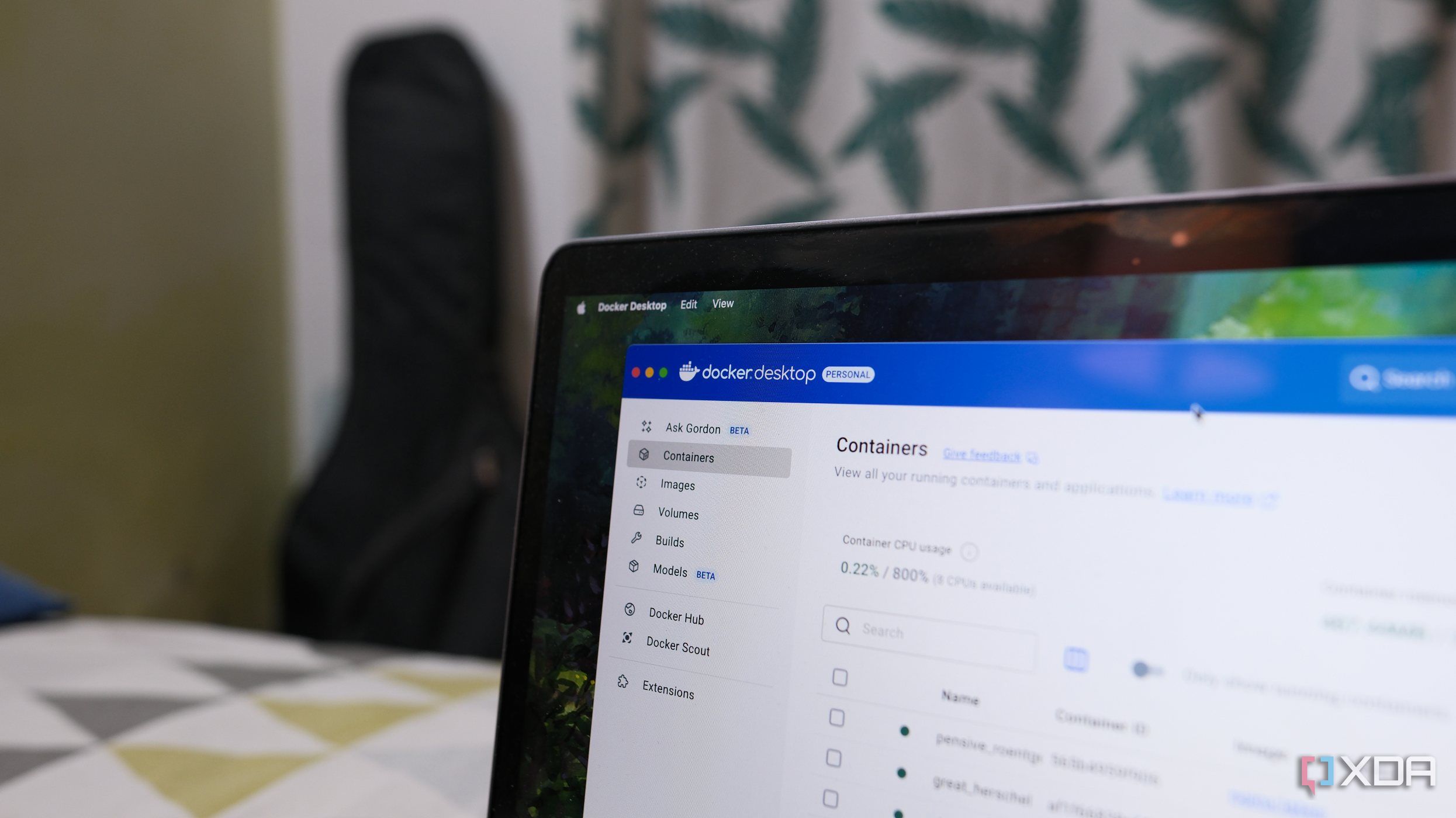

The State Water Resources Control Board is expected to finalize its decision soon. If the Bay-Delta Plan is approved, implementation will occur over several years, with agencies required to submit compliance plans, adjust operations, and brace for likely legal challenges from various stakeholders.