GANZHOU, China — China’s control over critical minerals has emerged as a pivotal factor in recent trade negotiations between Beijing and Washington. The talks concluded with both parties announcing a framework to pursue a deal, underscoring the strategic importance of these resources in global supply chains.

For decades, China has meticulously developed the world’s leading industrial chain for mining and processing critical minerals, essential components in electronics, advanced manufacturing, defense, and healthcare industries. This dominance is particularly evident in Ganzhou, a key production hub for rare earths, where the local economy thrives on mining and processing these valuable resources.

Critical Minerals as a Trade Issue

In response to escalating tariffs and controls on advanced technology, China has mandated that exporters of certain rare earths and critical minerals obtain licenses for each shipment. This regulatory requirement has led to supply chain disruptions in the U.S. and other countries, as approvals can take weeks.

President Donald Trump announced that China would ease access for American industries to obtain essential magnets and rare earth minerals, facilitating ongoing trade discussions between the two largest global economies. In exchange, the U.S. agreed to halt efforts to revoke visas for Chinese nationals on American campuses. However, the specifics of the agreement remain unclear, with no confirmation from Beijing or formal approval from Chinese President Xi Jinping and President Trump.

The Chinese Commerce Ministry recently stated it had approved a “certain number” of export licenses for rare earth products, acknowledging Trump’s request to Xi during a recent phone call. Additionally, JL MAG Rare-Earth Co., based in Ganzhou, confirmed it had secured export licenses for shipments to the U.S., Europe, and Southeast Asia.

“Without the removal of tariffs on Chinese goods, it will be difficult to blame China for continuing to strengthen its export controls,” said Wang Yiwei, a professor of international affairs at Renmin University.

An Industry Built Over Decades

China’s strategic focus on rare earths dates back to 1992, when Deng Xiaoping highlighted their importance by stating, “The Middle East has oil, China has rare earths.” This vision has driven Beijing to integrate rare earths into its economic security strategy. In 2019, Xi Jinping underscored their significance during a visit to a processing plant in Ganzhou, calling them a “vital strategic resource.”

Today, China holds a near-monopoly on “heavy rare earths,” crucial for producing powerful magnets used in defense and electric vehicles. The country also dominates the production of tungsten, gallium, antimony, and germanium, essential for semiconductors and other advanced technologies.

The risks of relying on Chinese suppliers became apparent in 2010 when Beijing halted rare earth exports to Japan over a territorial dispute. This led Japan to diversify its supply sources and invest in processing plants abroad.

China’s export license requirements for critical minerals have pressured global electronics manufacturers and automakers. In Europe, some auto parts makers have shut down production lines due to supply delays, while Tesla CEO Elon Musk has cited rare earth shortages as a challenge for his company’s robotics projects.

China’s Dwindling Resources and Global Implications

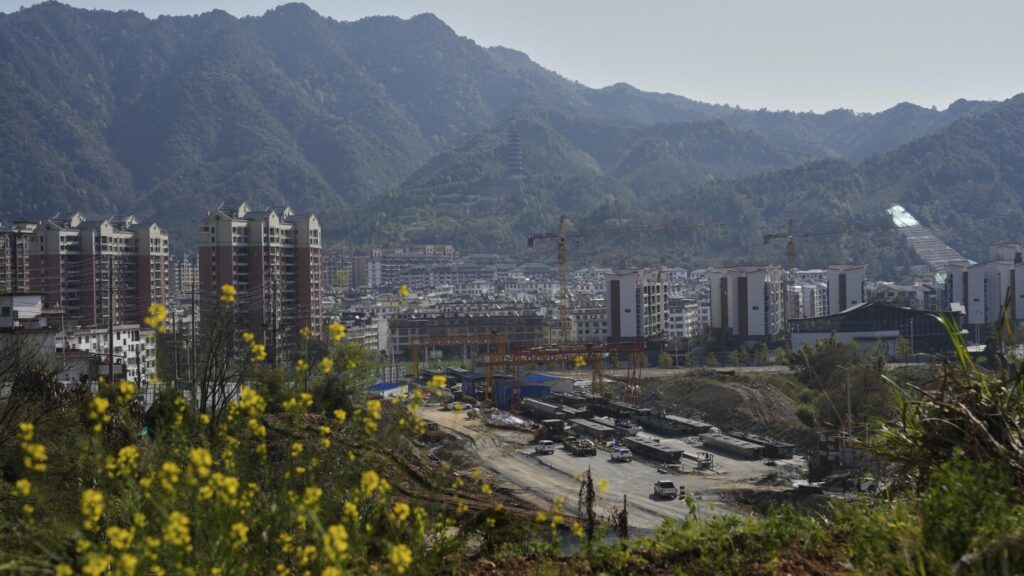

In Ganzhou, nestled in the Dayu Mountains, the U.S.-China trade war is a distant concern compared to the depleting mineral resources. Local miners and traders express growing worries about the sustainability of their industry as resources dwindle.

Zhong, a tungsten factory manager, noted increasing difficulties in sourcing tungsten, an ultra-hard metal used in various high-tech applications. “Smaller mines and trading companies are disappearing as resources dwindle,” he said.

According to state media, at least five tungsten mines have closed in the area in recent years. Remaining reserves are deeper and more challenging to extract, prompting processing factories to source materials from other provinces and countries like Africa and Cambodia.

Despite these challenges, major companies in Ganzhou are investing abroad to secure resources. For instance, Ganzhou Haisheng announced a $25 million investment in a new tungsten plant in Thailand.

“China will likely maintain its dominance in critical minerals,” said Fabian Villalobos, an engineer and critical minerals expert at the RAND think tank.

The U.S. Struggles to Catch Up

Between 2020 and 2023, the U.S. imported at least 70% of its rare earth compounds from China, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. While the U.S. has diversified its sources, it remains heavily reliant on China.

President Trump has prioritized improving access to critical minerals as a national security issue. However, the U.S. faces significant challenges in developing its supply chain. The sole operational U.S. rare earth mine, located in Mountain Pass, California, lacks the capability to process heavy rare earths and sends its ore to China for processing.

The U.S. Defense Department has invested $439 million to build domestic rare earth supply chains, but experts warn that replicating China’s industrial chain could take decades.

“There are going to be real issues unless we can figure out how to get along with China while developing our resources,” said Mark Smith, former head of the Mountain Pass mine.

The focus on critical minerals presents opportunities for smaller miners to invest in extracting and processing niche minerals like tungsten. “For many companies, the strategy hinges on a scenario where U.S.-China relations become more confrontational,” said Milo McBride, a sustainability and geopolitics expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

As global demand for critical minerals continues to rise, the geopolitical landscape surrounding these resources remains dynamic and fraught with challenges.